Articles

Photographic memory: the revival of an artefact.

Text: Tom Wilkinson.

The private antecedent to coffee-table tomes on Soviet Modernism, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg’s photo book is reproduced as an artefact from an ever more distant moment in time ...

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg: Series and Transformations

Simon Baker

‘When the combat ceases, that which is does not disappear, but the world turns away.’ Paul Virilio uses these words from Martin Heidegger to introduce his 1975 book Bunker Archaeology. Comprised of the author’s own photographs (taken between 1958 and 1965), maps and other documents, it offers a radical reappraisal of the 15,000 defensive concrete structures left along the coasts of France by the occupying German forces during the Second World War. Radical not because of Virilio’s cultural politics, (which he would develop in later, more provocative texts), but because Bunker Archaeology fuses research and apparently ‘documentary’ photographs with a sculptural sensitivity that seems derived more from the minimalist avant-garde than a conventional history of military architecture.

It is tempting to imagine that Virilio, in the late 1950s, had already somehow ‘seen’ the photographic archaeologies of Bernd and Hilla Becher, whose typologies of soon-to-be-defunct industrial structures transformed the art world’s understanding of the relationship between sculpture and photography in the 1960s. But if Virilio’s chapter titles ‘Series and Transformations’ or ‘An Aesthetics of Disappearance’ could also have described the Bechers’ work, it is perhaps because between the time he took his own photographs and published his book the Becher’s grids and series had become a reference of sorts. Arguably then, having been brought into being after their success in Europe and inclusion in the influential American ‘New Topographics’ exhibition, Virilio’s book can be understood as both predating and post-dating, so perhaps ‘spanning’, the emergence of a new conception of the complex relationship between photography, research and aesthetics.

Evidently however, the spaces between photography, research and aesthetics, like the spaces between combat, disappearance, and turning away, are as appropriate to the work of Ursula Schulz-Dornburg as they were to Virilio’s prescient and important book. Her practice, over more than half a century, has relentlessly returned to sites of social, political and cultural conflict with an approach that combines the curiosity and erudition of an academic, with the systematic process and formal rigor of a minimalist, or even conceptual, artist. As likely to know an obscure date about the early history of the Middle-East as the precise text of a work by (her friend) Laurence Weiner, and totally detached from the Bechers’ Dusseldorf ‘school’, despite living in the city for much of her life, Schulz-Dornburg is an enigmatic outsider in whichever field she chooses to operate.

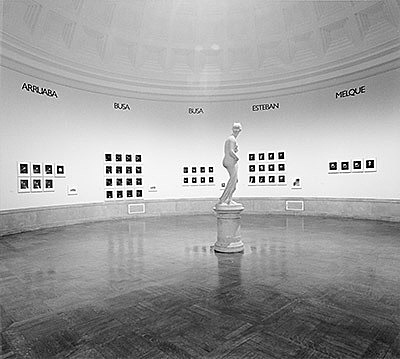

Coincidentally, (or not…), 1975, the date of Virilio’s book and the exhibition which it accompanied at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, was also the year in which Schulz-Dornburg exhibited her series ‘Vorhänge am Markusplatz in Venedig’ (Curtains in St Marks Place, Venice). A striking and beautiful body of work, it already embodied so many of the qualities that would mark out Schulz-Dornburg’s career-long practice: a series of modestly scaled, technically stunning photographic prints that offer an informed and sensitive account of a subject than brings together architecture, its context, use and transformation over time, with the ability of the camera (in the hands of an artist) to allow us to see and understand the ignored or overlooked. With an approach that could be understood in a venerable topographic tradition from Charles Marville to Eugène Atget in France, George Barnard and Timothy O’Sullivan to Walker Evans in the USA, and to Albert Renger-Patzsch in Germany, Schulz-Dornburg has staked out her own unique photographic landscape in which disappearance, absence and endurance are registered across vast stretches of distance and time. From Venice in the 1970s, to Iraq in 1980, Spain in the early 1990s and then Armenia repeatedly from the late ‘90s to the second decade of the twenty-first century and then more recently Syria and Kazachstan -Schulz-Dornburg has not only travelled widely, and with profound engagement and commitment, but she has built up long-term relationships with the places and people she has photographed. Far from some kind of post-conceptual humanism, however, the results of this investment of time and effort continue to manifest themselves as restrained and formally sophisticated installations of quiet, poetic, often apparently empty, black and white photographs: images that offer difficult questions in place of simple answers.

Although there are multiple threads and connections between the various aspects of her practice there are perhaps three essential set of concerns that we might identify as being of consistent importance to Schulz-Dornburg. Her work in Iraq and Mesopotamia, Georgia and Azerbaijan, relates directly to questions of boundaries and borders, the shifts of power as empires rise and fall, and the effects of these changes on the landscapes and peoples that live in them. In her key series ‘Transit Sites’ (in Armenia) and on the Hejaz Railway between Medina and Jordan, she investigates the specifics of architecture and infrastructure, especially as it relates to notions of mobility and movement; opposed by the stubborn resistance and longevity of outmoded and defunct architectural forms. Finally, in her work around nuclear test sites in the former Soviet Union and the wheat archive of the Vavilov Institute in St Petersburg, she brings into focus the relationship between political contingencies and environmental devastation (or the destruction of natural resources) highlighting the political stakes in man-managed, or manabused, landscapes. But beyond these evident concerns and commitments, there is also a subtle, beguiling and absorbing poetry in Schulz-Dornburg’s attention to the most essential formal properties of the photographic medium: to the effects of light on, and in, space; to focus over distance under shifting patterns of atmosphere and weather; and to the uncanny ability of photography to produce sculptural forms from even the least promising raw materials. For, despite the politics and social engagement that has underpinned her career, it is, finally, Schulz-Dornburg’s sensitivity and sophistication as a visual artist, a consistent and unswerving commitment to formal concerns, and to the rhetoric of presentation (whether on the wall, the screen, or the page) that transcends her documentary and archival impulses. As such, the stories that Schulz-Dornburg discovers, investigates and brings back to us, whether of combat, conflict, trauma, disappearance, or the ebb and flow of power over time, become stories from which we no longer seek to turn away or forget; but instead, turn towards and learn to remember.

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg:

scenari su un futuro ineludibile

Pino Musi

The Best Photo Books of 2018.

Teju Cole, New York Times Magazine, 2018

... Schulz-Dornburg, ... work is motivated by a consistent imaginative quest: how to photograph landscapes in political transition ...

‘The craze for images of Communist architecture can be traced back to the work of one intrepid photographer’

Tom Wilkinson

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg shares the typological obsession of the Bechers but her aims are quite different ...

Time and the Desert of Ambition: Ursula Schulz Dornburg’s Some Works

By Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

An Interview With Ursula Schulz-Dornburg

Becky Rynor, National Gallery of Canada | Magazine

Two Faces of Different Worlds

Edward Lewis

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg is taking time out on the roof of the Windsor Palace rooftop garden watching fisherman toil in the murky waters of Alexandria’s eastern harbor to explain the origins of her latest exhibition.

She is a busy woman and her current exhibition, “Sonnenstand” alongside Egyptian artist Bahaa Medcour’s “Two Faces of Eternity” is currently showing at Bibliotheca Alexandrina and sponsored by the Goethe Institute.

She recently exhibited in Bilbao and Paris before returning to Düsseldorf, her native city. Ursula’s also putting the finishing touches on the next big event due in January 2009, an exhibition in Munich alongside celebrated Polish artist Miroslav Balka.

At first glance, Ursula’s photographs strike the viewer with their several references to contemporary society and the overriding sense of loss and disappointment seen firsthand by the celebrated photographer. The images are shot in black and white, accompanied by some literature from well-known artists including the conceptualist artist Lawrence Weiner.

Four months prior to the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War, Ursula was photographing the marshes and remarkable archaeological sites of one of the world’s oldest civilizations. The devastation and disappearance of such beauty left an impression on her that has lingered throughout her career. As her exhibits go from Europe to the US, she continues to explore other diverse cultures such as Burma, Russia, Armenia, Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Yet it was during her trip to Iraq that Ursula started researching Arab influence on Christian architecture, which is the main theme of her latest exhibition.

Central to the exhibition is the Cordoba Calendar that is displayed in Arabic within the exhibition hall. The calendar, believed to date to the 10th century, includes important dates and festivals of both Muslim and Christian faiths.

Ursula used the calendar to tie together the many themes of the exhibition, including life, light, seasons and cycles, astronomy, enlightenment and the complexity of human nature.

Seven blown up shots of various species of seeds echo the feeling of loss and struggle. The seeds were a difficult subject to capture due to their size and were photographed in a fashion that makes them look like they’re shaking; a technique that Ursula admits was time consuming.

Ursula said seeds were chosen because they represent one of the most basic and fundamental elements of life. They were taken from a seed bank, highlighting the current threats including genetic modification and the delicate balance of the seasons. A quote that reads “Stars don’t stay still for anybody” splits the photographs on a large panel, once again highlighting the idea that we are governed by the earth’s cycle and not the other way around.

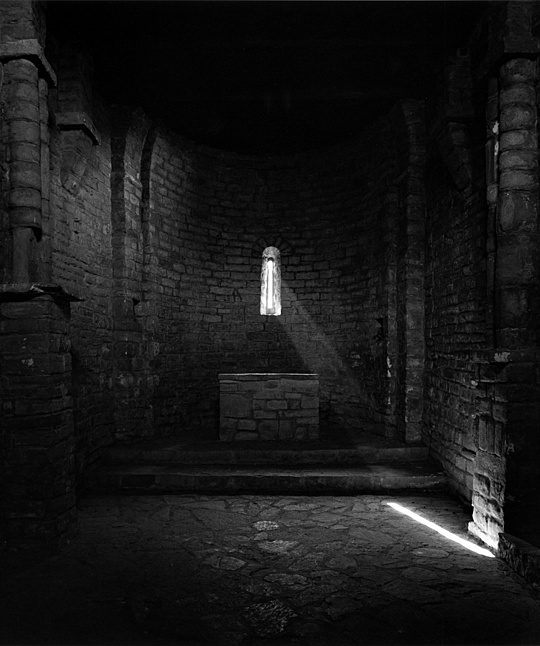

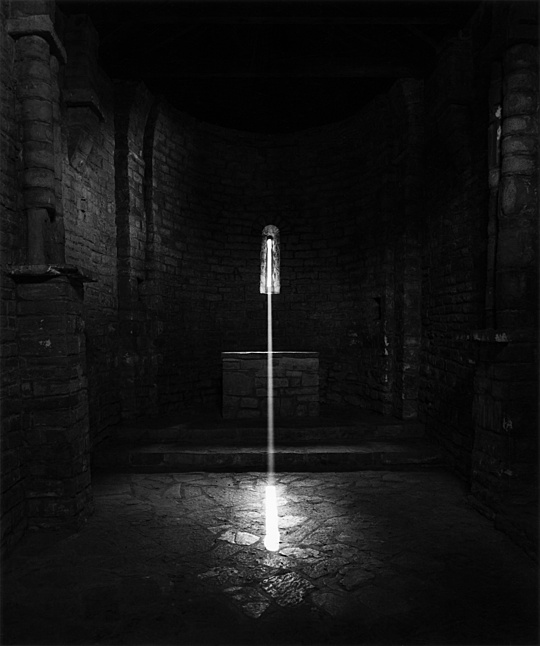

The following section of the exhibition includes shots of 10th and 11th century Spanish hermitages. Despite being a Christian sanctuary, their design is subtly influenced by Islamic architecture and highlights the intricate multi-faith relationships that existed during the period.

The role and cycle of the sun is captured in the sequences that illustrate the differing positions of light illuminating the dark interior. Ursula said that the concept came to her while she sat on the cold floor of a hermitage in Estaban, summing up the experience by quoting a well known saying, “If you travel by car you see nothing, if you walk you see more and if you sit on the side of the road you see all.”

On the adjacent walls of the Bibliotheca’s exhibition hall hangs Bahaa Medcour’s work entitled “The Face of Eternity.” Photography has been a passion for the electrical engineer, who said that he can’t remember the last day that went by without him using a camera.

The subject of Medcour’s exhibitions have included the Great Pyramid, Philae and Rome’s Coliseum.

The 47 colored prints focus on one of Egypt’s most famous edifices, the Great Pyramid, and the stunning tombs of the southern village of Hiw, some 550 km south of Cairo. As you look over the shots, you are immediately struck by the apparent differences of the subjects — one is an immense stone structure designed for the elite, the other very small and modest clay tombs. Still, he said, they are both ‘houses of eternity’ and therefore one of the overriding themes of his exhibition is unity.

The images, most of which have never been printed before, capture the Great Pyramid in a unique way. Medcour is well aware of the difficulties of photographing a subject that has been covered to death, but his approach, focusing on interesting details of the pyramid and not shooting it in its entirety.

“Every stone deserves more than a second look. Every shadow needs to be studied. Every angle needs to be measured. So many aspects of this Great Pyramid are still ignored till this day.”

The exhibit’s other focus, the tombs of Hiw (nicknamed the merry tombs due to the use of color by the villagers) provide some remarkable images of the graves and simple architecture of the cemetery. Many of the prints, said Bahaa, compliment those of the pyramids thus highlighting the notion of unity between the two subjects.

First displayed in the Egyptian Academy of Arts in 1984, the first photographer to do so, Bahaa has been to Hiw four times and exhibited these images extensively, including inaugurating the exhibition hall in the museum of Turin, as well as being included in numerous magazines.

By Edward Lewis, Daily News Egypt, First Published: October 9, 2008

Seeing What Is Missing. Time in Stone

Jan Thorn-Prikker

Galerie Sabine Knust, München, 2006

All questions, all answers, repudiate one another.

To all questions different answers.

Alberto Giacometti

In 1977 Ursula Schulz-Dornburg travelled to South-East Asia and returned home with a series of photographs depicting twenty five ravaged sculptures of the Buddha. It almost seems as if she arrived in Burma bringing the photographs she took there, as if inner images had preceded her pictures. She was in that country, a military dictatorship and to the present day still one of the world’s poorest states, to visit the unique architectural landscape of Pagan. Almost a thousand years ago Pagan was a Buddhist kingdom, a flourishing realm devoting a great part of its wealth to worship of the Buddha. The decline that has continued up to the present day got under way after an onslaught by Kublai Khan, Prince of the Mongols, in the year 1287. Hundreds and hundreds of temples and stupas, slowly falling into ruin, stand on this high plateau extending over several dozen square kilometres. This is a landscape of rare magic.

For the most part Ursula Schulz-Dornburg did not photograph the landscape. Instead she concentrated on the aura of this place, shaped by thousands of statues of the Buddha. The sight of these wounded bodies in stone so impressed her that now, almost thirty years later, she has returned to the images produced then.

Almost all of her photographs repeat the same image. So far as possible all these pictures were taken from the same distance. They avoid all effects and refrain from any intervention. Just light on paper, black on white, contemplation as a basic attitude, and reality as citation.

All of a sudden these photographs are linked by their stoic seriality. They appear like variations of what is always the same. This series of pictures makes visible something that characterises all photography. Each image can only be part of a greater whole which eludes being photographed. The special feature of this series is its theme of absence. The photographs show us that something is missing. They focus on this absence. It is as if their magic is derived precisely from what is not there. They depict a present absence.

These statues lose their history. Their religious context is reduced to what is visible. The people who once produced these objects have vanished in their depiction. Everything essential is invisible. And yet there still remains a quintessential residue.

We see twenty five sacred sculptures revealing visible traces of violent mutilation. We cannot be completely sure whether this is the outcome of looters’ acquisitiveness or simply of the ravages of time with its many forms of higher destructiveness. We can make assumptions but much remains obscure. These figures look as if they had been truly eviscerated. Some heads were chopped off. Other sculptures have a hole in the heart area or the stomach was brutally opened up. No-one need say to these objects: “Show thy wounds”. They reveal these wounds visibly and mysteriously. These are wounds in stone.

However the traces of destruction reveal only half the truth. The act of violence is not as yet fully accomplished. Almost automatically the observer’s gaze adds what is missing: the chopped off arms, the missing head, the eviscerated body. The gaze immediately restores the dismembered contours. It wants intactness. The part seeks the whole. The fragment functions as a sketch that complements itself. Seeing entails re-establishing. Reproduction and reconstruction are one. We see the past and an opportunity of surviving time – despite everything. Eternity and nothingness.

As photographs these sculptures are double-images. When we look at the gaping wounds with their deep fissures and lacerations, they suddenly become negatives of what has been cut away. It seems as if these figures are indestructible. But of course all that is just illusion. These are reproduced reproductions of spirit. The stupas themselves are intended to depict the cosmos. Mandalas as architecture. The immaterial in material form.

These images come and go in a pulsation that seems to stop the breathing of time. Just as in Giacometti’s great sculptures where the appearance of a living person asserts itself across infinite distance. For brief moments the invisible becomes visible and then immediately vanishes again. Everything changes unceasingly.

Violence – existence undergoing transformation.

Photographs are fragments. They never show the whole picture. However the Buddhas aimed at completeness. They sought an enlightenment for which no picture exists. All that remains for us are abstractions mediated by way of material relics. We only see the faded traces of history in decaying stone. But even in these vandalized embodiments there still remains something of a great tranquillity. We see a silence that has survived for centuries, an expression that does not pass away. The great composure that others wanted to destroy reasserts itself. We see the cycles of time.

These fragments are sketches in stone giving us space to fill them with our own imaginings. By contemplating these ruptured figures, to some extent we enter into them. Seeing is projection. What was once spirit decays and arises anew in the act of seeing.

A magical transmission of power and energy still survives. Behind a visible figure there appears an invisible one. We see how tradition functions. Something is passed on. Suffering without lamentation. We observe a seeing that has long passed away and constantly renews itself. We see what is most transient in a durable form. We contemplate an invisible portrait.

In this case art is an almost artless art. It is an art of looking, of attentiveness resisting a vanishing.

Jan Thorn-Prikker, 13.9.2006, Translation: Tim Nevill

Light and Place

Kosme de Barañano, 2002

"You will not return. Remember, turn not aside,

as you journey, from what is so simple

to appreciate: this wheat and the house"

SALVADOR ESPRlU, Llibre dels morts

Numerous exhibitions in Europe and the USA have brought international fame to the German photographer Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, whose work is now presented in Spain for the first time on such an extensive scale. The exhibition includes five series, created between 1980 and 2001, which show specific places in a basic, archetypal way: the interlocking cycles of time, represented in sculptural spaces of stone, light and dark that are caught up in a process of continual change, in the series Sonnenstand (Solar Position) and Grenzlandschaften (Borderscapes); the line of the horizon between water and sky in Verschwundene Landschaft (Vanished Landscape), the landscape of the Tigris in ancient Mesopotamia; the travails of waiting at bus stops in the middle of nowhere, in the series Transitorte (Transitsites); the extreme situations in the Arctic reproduced in dioramas In a museum in St Petersburg, in Erinnerungslandschaften (Memoryscapes).

These are silent situations, reduced to the absolute essential, developing from an inner core of emptiness and stillness. In this respect, Schulz-Dornburg's photographic work links up with one of the most important lines of development in modern art, for space appears here not as static volume but as dynamic process, and emptiness not as lack but rather as a horizon of events, a force field in which things appear and disappear: they are seen in the light of their finite nature.

In Schulz-Dornburg's photographic narratives there is a layering of fragmented, linear, cyclic, interwoven structures. The world of the image forms at the intersection between the places and situations experienced and the perceiving consciousness. These landscapes are both subjective and objective, illuminating flashes revealing situations of transition. Each kind of landscape has its own stories, endlessly mirroring each other in complex topographies.

The house is a perfect symbol of human existence on this planet. It is "our corner of the world", "our first cosmos", the "nerve centre of anthropological cosmology", as Bachelard says in La Poétique de l'espace (P.U.F., Paris 1957). In this sense, the "house" (Haus) may be a cave where a hermit meditates in the Transcaucasus or a chapel on the Camino de Santiago in the Pyrenees, a floating reed-house in the marshes of the Tigris, a tent on an ice floe drifting in the Arctic, or a bus stop. In a world of huge movements of migration, in a turmoil of unparalleled, new, nomadic mobility, we find ourselves reduced again to ignorance about what the philosopher Martin Heidegger described as "dwelling" (wohnen): "our human way of being [sein] on the Earth" (Heidegger, M.: "Bauen Wohnen Denken", in Heidegger, M.: Vorträge und Aufsätze). And for him this is dearly bound up with our condition of mortality.

Schulz-Dornburg shows images of this world, eternal images that reach beyond time. Images from the borders of the globalised world: a temenos, a sacred place in every part of the landscape. Yet as if the borders were also the centre, and the centre extending everywhere.

Kosme de Barañano

Published in A través los Territorios / Across the territories / Fotografias / Photographs 1980-2002

Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno / Valencia

Living in Transitions

Photo Series by Ursula Schulz-Dornburg

Matthias Bärmann, 2002

"The houses of mankind form constellations on earth."

(Gaston Bachelard)"[ ... ] for many things here overlap and coexist."

(W. G. Sebald)"Where the heart lies, one carries memories around like a hole."

(Diane Glancy)

Travelling with the requirement of exposing oneself physically and mentally, allowing oneself to be drawn completely into otherness. Becoming so strange to oneself that it is only then that one really first comes to oneself. For Ursula Schulz-Dornburg taking photographs is synonymous with being on the move, and her photographic investigation always takes the form of a series of shots. As they are portrayed, topographies develop into combinations containing many different perspectives and layers. Even though not a single person is to be seen in many of the series, these places are always inhabited places, or places formerly inhabited, albeit in the most remote antiquity. They are "settled" places, where even in individual features, even in faint traces, the human element present is like a resolute gesture of living in the world. But above all they are, both externally and internally, archetypal places. Here seeing means seeing again, and recognising, according to Plato, is recognising again — an interplay between external and internal image along the lines of déjá vu. Thus there are two simultaneous movements that correspond to one another, outwards and inwards, expanding and contracting: a movement into the distance that is matched by an inner concentration — a complementary movement of life. The camera acts as a medium between them: a casing, cave, camera obscura or black box. An interface between inside and outside. As a small physical object, the camera itself is also, in passing, a reflection of the motif that constantly runs through all of Ursula Schulz-Dornburg's work: the architectural motif of the house as a place of human dwelling, of persisting in time. An internal and external place of refuge. These two aspects come together in the photographs. Thus each picture is also always a kind of self-portrait. Becoming what one already is.

Der Tigris des alten Mesopotamien (The Tigris of Ancient Mesopotamia). This was the oldest cultivated region in the world, almost unaltered for six thousand years. The garden of Eden, where time stood still. A land between two rivers, the waters of the Euphrates and the Tigris, which made agriculture possible in the wilderness. In 1980, at the outbreak of war between Iraq and Iran, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg photographed the marsh country in the lower reaches of the Tigris, the amphibious realm of the Ma'dan, one of the most ancient civilisations still existing in the world at that time. A realm of water, sky, horizon and reeds. On small islands in the water, woven out of reeds and set in among the reeds, stand the muhdif, light nomad constructions of which it is hard to say whether they are boats that have come to a temporary halt or houses that are about to cast off. At any moment more reeds can be added, in a living process in which they endure by virtue of their transitory nature. The beauty and skill that they reveal are the direct result of the simplicity and functionality of their woven construction. The enduring existence of the dwelling and its temporary nature are closely bound together in the architecture of the muhdif, as also are absoluteness and provisionality, isolation and openness. These reed structures were engraved as images on old stone stele that are now five thousand years old. In the Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh, one of the most ancient texts in human history, the origins of which go back to about 2100 B.C. and which, like the muhdif, was kept alive for thousands of years, a god, not being able to impart a warning directly to men, addresses it to the house made out of reeds:

"Reed-hut, reed-hut! Wall! Wall! / Reed-hut, hearken! Wall, reflect! / Man of Shuruppak, son of Ubar-Tutu, / Tear down [this] house, build a ship! / Give up possessions, seek thou life. / Despise property and keep the soul alive! / Aboard the ship take thou the seed of all living things."

Power originating from a spirit of fear. The story of Gilgamesh, the ruler of Uruk, presents a drama that deals with dwelling in the world, the transition from the life of the nomad to settled existence. His deeds — the construction of mighty city walls, the clearing of the Forest of Cedar, his attempt to eradicate all evil from the land — are the classic projects of cultural heroes. What drives him on is the awareness of his mortality, for although he is predominantly a god, he also has a small portion of humanity, sufficient to make him mortal. The fear of death is like a thorn sticking in his flesh, goading him to search restlessly for eternal life, which in the end he finds, only to lose it again immediately. "It is not power that corrupts," says Aung San Suu Kyi, the Burmese civil rights campaigner and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, "but fear. Fear of losing control." One who no longer lives by the natural rhythms of the nomad must take over control of things. In the end he is seized by fear of losing control, fear of losing himself, fear of death.¹

Verschwundene Landschaft (Vanished Landscape). "Photographers deal in things which are continually vanishing," as Henri Cartier-Bresson said, precisely indicating the time-related basis of the process of photography. In Ursula Schulz-Dornburg's work, vanishing is present in many different forms. In this particular case, a contributory element is the fact that the dictator in Baghdad, Saddam Hussein, drained the marshes in only twenty years, thus depriving their inhabitants, the Shiite Ma'dan, of the basic means of existence, persecuting and killing them. For a dictator it was too hard to see what was going on in the floating in-between realm of the world of reeds, too hard to control the highly independent thoughts of its dwellers about matters of life and death. Men, animals and plants have vanished, and where the muhdif once were there are now motorways, military checkpoints, intensive agriculture and houses, the same as everywhere else. The blocking of the waters of the Euphrates and the Tigris, retained in the reservoirs of the dams that were built in the course of the Turkish project in the upper reaches of the two rivers in South Anatolia, have contributed further to the disaster. Where the water ends, no land begins. Ursula Schulz-Dornburg photographed the marshes in black and white, archaic and clear, and in the light tones of the prints of the images she also takes them away. The ancient cultivated land is present here as it vanishes; someone who understands this pain does not need to see all the gory details. These topographies are shown as being in the process of transition, at the beginning of disintegration. The line of the horizon abolishes all perspectives, dividing space into two realms, nothing and almost nothing, sky and an expanse of water, which are folded together in a mirror image of one another, becoming one inside and outside. Seen from the horizon as a boundary that in itself is nothing, these places reveal themselves in the light of their finiteness. The horizon, the "zero line of humanity" (Ursula Schulz-Dornburg). The horizon, "perhaps the home of all mankind" (Eduardo Chillida).

"The horizon is more a verb

than a noun"

(Lawrence Weiner)

The magnificent work Sonnenstand (Solar Position) was produced in 1991-92, while the Gulf War was being waged in the Middle East and bombs were falling on the marshes of the Euphrates and the Tigris. Ursula Schulz-Dornburg repeatedly travelled to the Pyrenees and took photographs in the interiors of small hermitages and chapels constructed in the tenth century. Nearby is the Camino de Santiago, the Road of St James, the pilgrim route of the Christian Middle Ages: the journey, the way. The spiritual world of these ermitas (from the Greek word eremos, desolate), with their Mozarabic stylistic elements, comes from Christian and Islamic devoutness. In the ninth century, the Córdoba of Al-Andalus was the intellectual centre of Europe, a common history now commemorated in Spain by the Fundación EI Legado Andalusí. The calendar of Córdoba establishes a relationship between the earthly cycles of plants, animals and men in the course of the seasons of the year and the stellar cycles of sun and moon. The everyday touches the universal, the specific place on Earth and the cosmos enclose one another. In his Republic, Cicero lets three friends talk together about what significance should be conceded to earthly matters in relation to heavenly phenomena, and he writes: "Yet our house is not confined to the space that our four walls enclose, our house is indeed the whole world."

How can one represent time in photography, making time visible as a rhythmical process? Conceptually, Sonnenstand is Ursula Schulz-Dornburg's most powerful work. Photographs that are veritable images of light. In the ermitas she took sequences of photographs at different times of the year and at different times of day. The installation of the work shows the sequences during a single day — and thus the rotation of the Earth — in their horizontal progression in rows; the vertical arrangement of the rows one above another corresponds to the passing of the year, the cyclic movement of the Earth around the sun. Rays of sunshine enter through narrow window recesses, feeling their way with time through these narrow spaces. The cycles of time appear in the interior as shifting configurations of light, space blends into the dimension of time. Through perception a space-time develops in which the rotations and orbits of the heavenly bodies converge with the rhythms of human life, macrocosm and microcosm. Matter and light become apparent to one another in the resistance that matter opposes to the entering rays of light: as walls, the solid stone block of the altar, heaps of rubble or the hard-packed earth floor. The arrangement of the architectural structure and the nature of the material modulate the manner in which light appears, entering in a tight beam like a laser ray, fanning out, seeping away in the darkness or spreading as a soft glow. Light and darkness in a process of constant transformation. The horizon, the boundary of mediation, is drawn inside. An interaction of architecture and cosmological order in processes of sheer mathematical beauty.²

Like all Ursula Schulz-Dornburg's projects, Sonnenstand has many different aspects and can accordingly be appreciated on many levels: as precise documentation, not least of loss, and at the same time as a committed vote for an open, intercultural view of things — a commitment that arises from preciseness and contemplation, with melancholy not far away — the ermitas are deteriorating or else being ruined by exaggerated restoration. Conceptually and aesthetically, the conditions of perception, and also those of self-perception, are reflected. Last but not least, although perhaps not expressly thus intended, the medium of photography is subtly picked out en passant (by itself) as a central theme: light, which enters the black box of the camera as it does in the dark chambers of the ermitas. The great seventeenth-century English philosopher John Locke described how the cavernous, room-sized camerae obscurae of his time exposed men to the uncertainty of a dark space, and thus really cut the ground beneath the supposedly sure stand point of the non-involved, objective observer. In 1922 Kazimir Malevich spoke of a "projection apparatus" that was both small and, at the same time, infinitely large: "The human skull displays infinity as the movement of ideas. It is like the endlessness of the universe [ ... ] and it houses a projection apparatus that makes bright points appear, like stars in space. In the human skull, everything rises and declines exactly as it does in the universe."

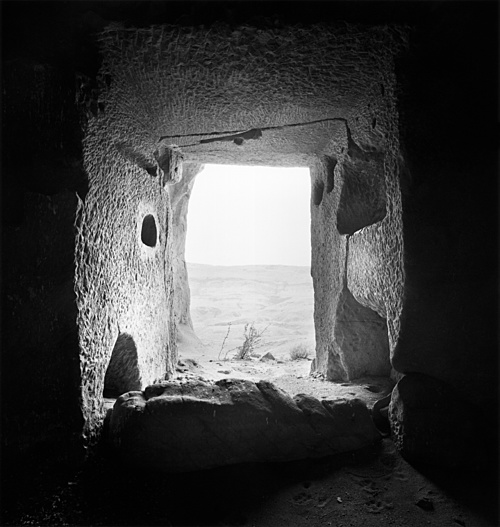

The series Grenzlandschaften (Borderscapes), 1998-2000, also shows interiors. Rock chambers, hermit cells, hacked out of the precipitous mountain face of the Transcaucasus in or after the sixth century by Christians who had emigrated from Syria. Bertubani, Udabno, Natlismtsemeli, Chichriduri, Zamebulo, Mrabalzkaro, Dodosrka, Muchrani, Saberejbi, Berebis Seri, Werangaredja. The concept of a boundary does not only refer to the modern frontier location of the caves between Georgia and Azerbaijan. Historically, they lay on a borderline between imposed and voluntary exile. And of course, in the solitude of extreme reclusion, there were also existential borderline experiences, physical and mental. Borderline experiences that also had to be brought to their conclusion so that these pictures could be created.

The caves could not be seen from outside. Inside, the rock walls of the cells are permeated by cracks and splits: this is a tectonic collision zone, an earthquake area. Seismic forces have tilted, compressed, stretched and torn apart the sedimented layers of stone. Inside the caves, stillness and mountain enclose the body like a stone womb. Shut up inside a cave in the mountain: the body as place, path and boundary. Embodied time, embodied space. Shut up in the cave of the body. Squeezed into this narrow space-the words angostura (narrowness) and angustia (anguish) share the same root. Perhaps the meditation on existence here was like Meister Eckhart's paradoxical description: "The more the soul collects itself, the narrower it becomes, and the narrower it is, the broader it becomes." A path through a narrow passage, gain through loss. Living in the world as a visitor, in transition, taking refuge "on the back of a tiger". In this existential exposure it is possible to experience a radical freedom that, by its very nature, reacts subversively towards any demand for power. In sequences, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg develops the entire phenomenological spectrum of these rock cells: traces in the fine sand of the cave floor, as distant as the first footprints on the surface of the moon; scars in the stone, made by chiselling or by tectonic movements; the interplay of light and darkness, which condense into abstract sculptural forms in space; the eye within looking outwards: the horizon — its horizontal line answered within by the vertical line of gravity.

Transitorte (Transitsites), 1997-2001, is a title that could be applied to the whole of Ursula Schulz-Dornburg's work. Bus stops in Armenia, the oldest Christian country in the world although nowadays nobody rightly knows where it belongs. Architectural elements constructed in the time of the Brezhnev era, some even earlier, as Communism's promise of a better world. Shelters between road and horizon, the boundary of settled territory and mountains, steppe and sheer nothingness. Places for waiting and people waiting, expressing solidarity in their temporality. The monstrous contradiction echoed in the very word "utopia": eutopos, the good place; and outopos, no place.

One of the bus stops is occupied by people who have come back from Germany, rejected asylum-seekers — "man spricht Deutsch" / "we speak German". At another bus stop a small cube has been constructed, set on pallets; this is where the shepherd lives. Many of the bus stops no longer provide shelter — iron frameworks through which the wind and weather pass, filigree ornaments, arching flourishes, calligraphy with or without people waiting, simply a sign for shelter. At any rate a sign, a reference point where one can stop and get one's bearings. A marker in space, on which time breaks. Waiting, nothing more. The people waiting, exposed to time, hold their ground, wait obediently and continue to hold out. Their raised faces, like the characters of a shifting, indecipherable text, are spelt out in a provisional eternity.³

Erinnerungslandschaften (Memoryscapes), 2000-01. "Remembering means having to retrace one's steps, totally alone, in a dried-up river bed" (Osip Mandelstam). One can see muffled-up figures, lost in a landscape of snow and ice. As if to confIrm a human presence in this wilderness, there are things: tents, meteorological instruments, sledges, a small boat, a ship, a plane and, of course, a flag, rammed into the ice. At first sight Ursula Schulz-Dornburg's photographs show this reality accurately, but after a brief irritation one realises that they are models that faithfully reproduce the original to scale. They are dioramas in the Museum of Arctic and Antarctic in St Petersburg, constructed in order to keep alive the memory of heroic events. The memory of the rescue by the Soviet icebreaker Krasin of the crew of the airship Italia, which had broken down during an attempt to fly over the North Pole in 1928, and the pilot Babushkin, who then became the first man to succeed in landing a glider on an ice floe. And the memory of scientific heroism: since the thirties the Soviets had had scientific research stations on ice floes drifting in the Arctic; those who went out there exposed themselves to a year of extreme silence, cold, darkness and loneliness in order to measure and record the flows of ice, wind and water and their own drifting through the cold heart of the planet.

The scenes were photographed with a simple amateur camera using a small film format (APS), and subsequently enlarged. The blurred quality resulting from this discrepancy gives the images the authenticity of photographs taken in extreme conditions, and at the same time an atmosphere of reverie: dream image and waking image blended together. Believable yet unreal. "The image comes from a collaboration between the real and the unreal" (Gaston Bachelard). This impression is further strengthened by the use of colour, which, as in the case of prints of early photographs that have later been coloured by hand, by its unreal transparency drives the subjects into the realm of the imagination instead of making them appear more realistic.

The photograph and the diorama share a common history. Louis Daguerre invented the diorama in 1822, and in 1837, by means of a chemical process, he succeeded in fixing the image produced by the camera obscura, with which painters had been working for many years. From the very start, both diorama and photograph were techniques for fixing moments, fIxing time. Memory itself plays no part in this process, it only comes later, in the act of looking at the image. "We cannot develop and print a memory" (Henri Cartier-Bresson). In transferring the Arctic scenes of the St Petersburg dioramas to photographs, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg commits a twofold breach of what is already an abundantly unreal reality. Thereby she provides access to a very personal, ambiguous world of images, which contains the inherent possibility of being a world of internal images, saturated with memories. The Erinnerungslandschaften — icy tableaux of isolation and solitude, distress and rescue — are images that scramble together both personal and collective memory. By introducing recollection and at the same time distancing it, they have the liberating effect of a Buster Keaton film: without any trace of irony, but human and comically heroic.

"Hold still — keep going"

"Now I travel maybe more inside than outside"

"The eye should learn to listen before it looks"

(Robert Frank)

The five series of photographs, created between 1980 and 2001, are related to a concept that is of great importance in Ursula Schulz-Dornburg's work: Shelter (Zuflucht). A concept that in the history of art and architecture in the twentieth century is associated with Henry Moore's "shelter books" — drawings of scenes in London Underground stations during the air-raids in the Second World War — and with alternative "shelter architecture" and its references to the constructions of earlier cultures, especially in the USA.⁴ Reed houses, caves and ermitas, bus stops, tents and research stations are examples of shelter architecture, each in its own particular way. In the images their presence is sharp and dear. At the same time they are existential metaphors for what the word "shelter" indicates: refuge, protection, sanctuary.

Shelter architecture interprets the existence of human beings on the Earth on an elementary level and places it in dialectical tension between self-assertion and exposure of oneself to risk. Steering between two poles of tension: a lifelong personal experiment with shifting parameters. The poet Georges Spyridaki expresses this wonderfully as he evokes an image of his house: "My house is diaphanous, but it is not of glass. It is more of the nature of vapour. Its walls contract and expand as I desire. At times, I draw them close about me like protective armour [ ... ] But at others I let the walls of my house blossom out in their own space, which is infinitely extensive." It is clear that here the poet is speaking of an inner house, an inner dwelling. This corresponds to the desire for an "internal structure", an inner refuge, which, according to Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, provides a strong impulse for her work. However, the possibility of withdrawal into an enclosed space, whether internal or external, requires a move in the opposite direction, as is made clear — with the ironic ambiguity of photography — by the Spanish word exposición, which means exhibition, but also exposing oneself, staking one's own life, and, last but not least, the time during which the film receives light, the exposure of the photograph.

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg's photographs are formally perfect, but she is not content with formal excellence. She combines the external elements of form and structure and documentation with a narrative approach, with history, and also with perception, alert intuition, reflection and recognition. She keeps this combination equally open to "outer" — the objective and general — and "inner" — the personal and special; and, in so doing, in her photographs she establishes depths that are also accessible to the observer in their many facets. Answers are not to be expected, of course, but rather, perhaps, the very same questions, always presented in new ways and perhaps more dearly, more decisively than before. The inexplicability of oneself is not resolved but liberatingly drawn into the realm of the ordinary, placed in context. On this path there is no certainty to be had, but instead, most probably, a resolute openness guided by alertness.

The dominance of the theme of architecture in Ursula Schulz-Dornburg's work is reminiscent, in terms of photography, of Karl Bloßfeldt, who photographed plants as fantastical architectural structures of geometrical strictness. With Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, the aspect of formal, compositional construction is scarcely of lesser importance. But it is consciously counterbalanced by a relational quality: her photographic series reveal a very varied, dynamic echo chamber of references and connotations. They evoke what is not visible (any longer), what has vanished or been lost, those who have retreated or departed, simultaneously and together with what is visible, with what (still) remains. In their existential openness, the people waiting in Transitorte mark the precise crossing point, a nomadic manner of living "in transition". The situations presented correspondingly embody places of transition, of in-between worlds, of borders. Transitory places. Places that derive their individuality not from their autonomy, their self-sufficiency, but from an interplay with many different references. They are characterised by the dynamic created when different realities engage together.

A paradigm emerges, the paradigm of an enlightenment resolutely broadened in its spectrum, with an urge for accuracy, objectivity and commitment that is drawn from contemplation; in other words, from awareness of the integration of the individual into its surrounding, living context. It is clear that such awareness reacts exceedingly critically towards the institutionalised practices of "culture". As has been explained by, for example, the Indian theorist on culture Homi Bhabha, a part in this is played by the concepts of imagination, memory and cultural interchange, and of course also the common field of ethics and aesthetics. The activity of art creates links — as is impressively exemplified by the many connections between the countless NGOs working throughout the world against the excesses of the process of globalisation — with other areas that produce knowledge and recognition, other areas of engagement. Ursula Schulz-Dornburg's places of shelter are more than a reflection of this — they anticipate this development, specifically in the focus on what is vanishing, what has been forgotten. Sometimes one must plunge into the past in order to re-emerge in the future. Or, rather, in the present, which throughout the world is characterised by voluntary or forced migration and all kinds of departure and exile. Movement in transition, remaining "in-between", the figure of the drifter: a reflection on our human condition as a visitor in time, which could be embodied in real freedom and solidarity.

MATTHIAS BÄRMANN

¹ Digression: Fear is certainly inherent in mankind from the very start of the history of our development, as a form of life that, in comparison with others, is born too soon. There also definitely seems to be a causal connection between fear and the formation of human intelligence. The situation becomes critical, however, when, in modem western civilisation, fear hardens into excessive safeguarding, an unparalleled mania for the protection of civilisation. Thus, for example, the "gated communities" of the American middle class are an expression of a quite neurotic need for security, as are the mobile high security camps that private American concerns are operating in Australia, for instance, in order to detain refugees in the desert: security, a service promising very high returns. But it must also be quite clear that the accelerated process of fortification and segregation in our lives is producing precisely the opposite effect, leaving us living more dangerously than before. Set against this, there is the insight that it is vulnerability that provides adaptability.

² Essentially, Sonnenstand is not far removed from Eduardo Chillida's great project on Fuerteventura, where a huge cube-shaped space is to be created inside the mountain of Tindaya. Chillida speaks of a twofold movement: the extraction of rock and matter, and at the same time the creation of emptiness in the heart of the mountain. Two shafts connect the interior with the exterior, leading the rhythms of light, sky and sea inwards. The visitor, a tiny figure in the huge empty cube, finds himself again between this universal context and the rhythms of his own body and mind.

³ The ambivalent situation of waiting, this removal from time and everyday activities, is also very well shown by the Kirghiz director Aktan Abdykalykov in his short film Beket (Bus Stop) (1995-2000). Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot begins with the words "Nothing to be done".

⁴ See, for example, Kern, Ken et al. (eds.): Shelter, 1973; Rudofsky, Bernard: The prodigious builders, 1977, and Architecture without architects, 1964; and Bourdon, David: Designing the earth, 1995.

Published in A través los Territorios / Across the territories / Fotografias / Photographs 1980-2002

Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno / Valencia

Across The Territories

Nomad Notes Towards The Constitution Of A Geopoetic Consciousness

Kenneth White, 2002

Preamble

Crossing the other day from France into Spain, I found myself in the area of the old customs post, the Aduana, not far from the banks of the Bidassoa. The old customs buildings are still there, but, thanks to the treaty of free circulation signed by fifteen or so European countries, they're now no more than vestiges. It's a strange feeling one has in such places today: half ghost town, half wasteland. It's like a garrison town when the garrison's gone. Like being in some inn at the end of the season — a bit outside time.

It struck me that this empty transition zone was the very image of our present cultural condition. The big trucks pass, new socioeconomic spaces are being created. There's a lot of movement and activity, even hyperactivity, in our sociocultural context too. But way down, at a deeper psychological, intellectual, artistic level, isn't there an emptiness, a hollowness?

Most of what we call "culture" consists simply in society's attempt to fill that hollow emptiness with noises and images, bitty information, infantile games, futilities, or an art that's lost all ground: one little invention after the other.

Objects circulate, but the deep passage is never made. The subject waits, as he has often waited: for the Second Coming, for the Revolution that will make history sing ... or for Godot.

The figure I'm going to call in these notes the nomad-geopoetician isn't content to wait. He/she is out to move, while never just jumping aboard the first vehicle that passes.

The nomad-geopoetician frequents all kinds of frontiers, broods along the borders, lights out for the limits — always in search of grounded space.

Frontiers are often the scars of history. One can go on harping about history (it's an industry), or else one can start to move outside history, seeing the old frontiers with new insight, envisaging space with new vision.

Seen in depth, a frontier is an area where forces meet and confront one another, but also where new forms emerge. It's a field of possibility. And there are questions in the air: what strategies? What works?

There are times when the question of "frontier", as distinct from the mere administrative management of boundaries, is the order of the day. Think of the expansion of the Roman Empire, with its limes, its confinia, its extremitates. And then look at its fall: the old unities are dislocated and broken, the frontiers float and dissolve. So is it with our civilisation today. A potential field is opening up. It's a question of political geography, certainly, but also of culture and aesthetics.

It's possible to discern here and there, the initial signs of a new spatial conscience. The spaces in question are historical, post-historical — also natural.

It's time, high time, to restore nature to its rightful place. History has had all its own way for too long. I'm not talking about any "going back" to nature. I'm just suggesting a few steps to the side.

That's a move from geopolitics to geopoetics. Geopolitics is based on the power relationship between State and State. Geopoetics is based on the living (biocosmopoetic) relationship between the human being and the Earth. The frontier here isn't situated between political unities, but between the human and the non-human.

There you have the ultimate frontier.

There you have the difficult area, the complex place, in which a new existential, philosophical and aesthetic space can be formed.

Is it not fairly obvious that what our culture lacks, at ground level, is a sensation of space? Wasn't art in its original impulse a perception of space, then of bodies moving across that space, then of moments in the course of that movement? And isn't it something of this nature we roust recover today, instead of merely accumulating "art objects" based on conceptules in a constricted context devoid of amplitude, lacking anything like an expansive poetics? Further to this spatiality as such, I wonder if we might not be able to envisage a specific space that would be neither mythical, metaphysical, religious, psychological, or merely technical: a space resonant with geopoetic tonality.

Such were the questions I was putting to myself the other day, in the wasteland of the Aduana, on the border.

And hence the investigation I intend to undertake here, accompanied by the photographs of Ursula Schulz-Dornburg drawn from hermitages along the old pilgrimage road of Santiago de Compostela, the border country between Georgia and Azerbaijan, a string of bus-stops in Armenia, the lost landscape of a mesopotamia, and a bunch of research bases in the Arctic.

1. Paths of Stone and Light

The Pyrenees have always been both barrier and passage. Hence that line of frontier posts stretched out all along the chain from the Portus Veneris (port-Vendres) in the East to the puntas arenas of the West.

Remember Hannibal the African coming in against Rome through the Perthus. Later, the marches were Carolingian: marca hispanica, marca hesperica. Frontier fluctuations, boundary perturbations, Emperor confronting Emir, Cross dashing with Crescent. Frankish troops on the Southern Front, Saracen troops on the Northern Front.

When the Regnum Francorum, the Carolingian empire, began to collapse and crumble, the nationalisms arose, in Catalonia, in Navarre: ethnic complexes, territorial identities, soul and soil. An old story. The old story — history.

Transcended only, if at all (politics and religion can get so dose) by those pilgrims carrying a shell to Compostela.

Over paths of stone and light.

I was once a great frequenter of the Ossau valley. A narrow corridor, with only the bottom land turned over. On the heights, up above Laruns, agriculture comes to an end. Serrated ridges, craggy peaks, perpetual snow at 7000 feet. Pile-ups of boulders from Ice Age rivers.

Arudy stands at the entrance where, in a cave, were found rocks, pebbles engraved with horses and reindeer. We're on transhumance tracks, and among the most ancient sanctuaries of humanity. At a crossing of roads, a dolmen. Over there, another, placed on a little plateau looking out to the sun. Elsewhere, cromlechs, stone-circles: in the early days of the twentieth century, shepherds still built such stone circles around their huts.

Those raised stones constitute the first great road of stone and light, marking passage-ways as well as the gathering of upright people, indicating a relationship between soil and sun, earth and star.

I like to think of those raised stones as "the Atlantic stones". They've marked the Atlantic coastline for millennia and I've followed their megalithic cartography all the way from Portugal up to the Scottish archipelagoes. But I know they go farther back than the Atlantic. The Atlantic is what they face, but their background is Anatolia. Out from Anatolia, the migration went to those lands later, much later, known as Italy, Sicily, Sardinia, Spain, France, the Armorican peninsula (where there seems to be a peculiar concentration), England, Ireland, Scotland, Denmark, Sweden, Finland ... The big stone road. One must imagine great monotonous stretches of uncharted, unnamed territory, vast eroded plateaus and postglacial beaches. The time is the end of the Boreal period, the beginning of the archaic times called Atlantic. Sudden mists, strange lights and lightnings — and up there, far above, moon, sun, stars: appearances, disappearances, constellations. The earthscape is mineral, dominated by great stone blocks fallen from obscure disasters, and by scatterings of fragmented rock. In such a context, geometry (a point, a line, a circle) can be a kind of salvation, especially if you can feel that you are establishing a correspondence with what you haven't yet called a cosmos.

It's a world of geometry and meteorology.

Later on, the stories come in: you hear of petrified armies, of druid sacrifices, all kinds of spookiness and collective unconscious archetypery. All this is what some people call "poetry". But the real poetics are elsewhere: in the open space, in the migratory movement, the elementary necessity, the primal gesture. It's a lot more interesting to try and read beyond the legends. Basically, let's never forget, we're concerned with a road of stone and light.

All over the mountains and the moorlands you also come across cup-marked stones. The cup, or cupula, was maybe at the beginning a simple hollow in the rock face — useful, say, for drinking dew. Later, some were maybe carved out, ritually, religiously, and offerings (of milk, of blood) may have been poured into them. Certain stones too, because of their shape or their position — an erratic block all alone on the landscape — might be considered sacred: peyras sacradas. It's the case with the Peyre Blanque (the White Stone) at the limits of the Lannemezan plateau. Such stones, often associated with thunder and lightning, would become culture-spots. And then there were those stones written on, engraved, the peyras escritas, bearing schematic designs: concentric circles, sun symbols. The theme of light is recurrent. An old song that used to be sung at wakes speaks of the union of Sun and Moon. Here's the chorus: Ech dio que eo dab lui se mardec atav estec — "the day when the Sun married the Moon, this took place". This took place. What? — the essential.

In time (it's a human, all-to human process), things get personalized, characters are invented: intercessors, intermediaries. Among the Cantabrians, the Basques and the Iberians, one hears of Abelio, the god of light, of Herauscoritze, the god of lightning, of Aherbelste, the god of the black rock, of Belenus, the god of the sun, and of his wife, Belisama, who drives the chariot of the moon, of Asteartia, in whose company, according to a highly disapproving ecclesiastic text of 905, "women fly over vast regions". When Christianity comes along, it brings in St Michael, St James, St John the Baptist, Mary Magdalene, the Virgin, to take their place. But ancient echoes remain, and, back of the echoes, the fundamental ground-tone. The Pilgrim Guide to Compostela informs us that when they want to say "God", the Basques use the word Ortzi, which means "the brilliant thing", the stormy sky. As is well enough known, the Christian chapels and hermitages were very often built on old pagan cult-places. Back beyond all the ideologies and representations, it's always stone and light the massive immobility of stone (geological zazen), the iconostasis of light.

That's how I see, ground, foreground and background, those strong images of stone and light that Schulz-Dornburg took in the hermitages of Clemente de la Tobeña, Arruaba and Juan de Busa, in the province of Huesca.

2. Transition territories

In his book of travel-sketches, Through Russia, Maxim Gorky presents the wanderers and vagabonds of the land, the "nowhere people" smitten with the craze for vagrancy. In socio-economic terms, those people are "useless". But, out on their "roads of a thousand versts", trying to satisfy their "need for space", they go beyond the boundaries of the common and the banal, and, at least at moments, they come to that state where being spaces itself out, where the soul is dissolved in the Void, "when one no longer thinks of oneself, but, on the contrary, issues from one's personality and begins to see with unwonted clarity".

All of those Russian wanderers gravitate gradually to the Caucasus, to the lands of Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan:

"How come you to be travelling the Caucasus?", we read in a passage of Through Russia.

"Everyone ends by heading for the Caucasus."

Rising up between two seas, the Black Sea and the Caspian, the Caucasus mountain-range, with its craggy peaks: Elbrus, Kazbek, Ushba, offers more than one parallel with the Pyrenees. Except for this: the Pyrenees constitute a frontier between two countries, whereas the Caucasus represents the frontier between two continents. If there was ever a place of passage, it's the Caucasus.

For the existential basis of these mountain lands, one has to think of the nomadism and provisional encampments of the Nogai and the Kalmuks, the horse-raising of the Kabards, the pastoral wandering of the Kurds, the Tatar shepherds digging themselves burrows to protect themselves from the biting wind that blows across the bare plateaux of the Karayaz. Other mountain peoples, wanderers over territory covered with absinth, grey mugwort and the blue flowers of delphinium, found shelter in a whole labyrinth of caves. As to the original Georgian house, it was a hole in the ground or in a rock, with walls of stone or brick, the roof consisting of a layer of day in which would grow all kinds of grasses, thus providing he at in winter and coolness in summer. The country is tough — marked by storms and earthquakes. Near Baku there's a field of inflammable gas: the "temple of fire" (we're in the neighborhood of Prometheus and Zoroaster). Above it all, Elbrus, in Tatar Yal-bouz, "the mane of ice". Even long Christianised, the Svans still kept the crypts of their chapels full of goat horns, and among the Khevsours, it was considered unfitting to let anyone die inside a house: one had to die facing the sun and the stars, one's last breath mingling with the wind.

In time, those who at the beginning called themselves perhaps simply gortzî, "the mountain folk", divided into strict ethnic groups, with strict religious ideologies: Georgians, Armenians, Ossetes, Circassians, Chechens, Abkhazs, Kabardians, Lezghians ... The Caucasus became what the Arab geographer Abulfeda called "the mountain of languages". According to Strabo, on the markets of Colchis (the basin of the Ingour), you could hear seventy different tongues. At the market of Mozdok, in the Terek country, the hill-folk of Dagestan would rub shoulders with the farmers of Kabarda and the Nogai nomads of the steppe. So long as, under the religious veneer, the old pagan ground remained, the common ground, the relationship to the land, so long as the general assemblies of the mountain, amounting often to republican communes, still survived, conflicts there certainly were, but they were rare and short lasting. Christianity (all kinds of Christianity) and Islam (all kinds of Islam) existed side by side.

And the movement continued, between Europe and Asia across the Caucasus, between the Caucasus and Persia, Anatolia. From earliest times, there had been the Greeks on one side (the Argonauts, Jason at their head, on the hunt for the Golden Fleece) and the Mongols on the other. Thereafter came the Byzantians, for whom the Caucasus was a place of exile (it was to the monastery of Pitzunda that the exiled Chrysostomos was travelling when he died on the road), nekrassovtzî Cossacks, Dukhobors ("spirit-fighters"), raskolniks, Arabs running away from their Turkish masters, Swabian colonists ... There were places of pilgrimage: the Vardzia monastery, "the castle of roses", hollowed out of the rock, the monastery of Nakhichevan (the "first house" in Armenian) supposed to have been boot by Noah himself, the monastery of Echmiadzin, that contained three hundred and sixty-five ancient manuscripts and whose bell bore an inscription in Tibetan: Om mani padme hum — "the jewel is on the lotus".

When the Russian Empire came on the scene, the "outside" land, the land of exile (and of skirmishes) became a land of total war — and extermination.

The central fortress of Russia in the Caucasus was Vladikavkaz. The great military highway between European Russia and Tiflis passed by there. All along this road, "the Line", were raised a series of Cossack stanitzas, strategic outposts and watchtowers. Garrison towns were created, such as Grozny ("the threatener"). At its inception, in 1777, Stavropol ("the city of the cross") was simply "No. 8". The tribes organized in self-defense, for example, the Chechen, under their chiefs Daud-Beg, Omar-Khan, Khaz-Mollah, and finally Chamil (Samuel), whose last stand took place on Mt Gunib. The Muslim saw in the Russian only the Christian; and for the Russians, the Muslims were no more than brigands and terrorists. The whole situation, as so often happens in history, became horribly, monumentally simplistic.

It was in the Caucasus that Lermontov situated his novel A Hero of our Time (1840). This is the story of Grigory Alexandrovich Pechorin, who describes himself as "an itinerant officer". The book consists partly of short episodic stories revealing facets of Pechorin's character and career, partly of travel-notes in which the country itself is very present. So it is that in the crossing of the Koyshaur valley, we hear of "a nameless torrent roaring in a black gully full of mist", and that in the vicinity of Gud-Gora, "it was so still all around you could trace a gnat's flight by the sound of its humming", while in the distance, over towards the south, rises "the great white form of the Elbruz". As to Grigory Alexandrovich Pechorin, the first thing to notice is the charged symbolism of his name: Grigory — Gregory the Illuminator, the Christian missionary; Alexandrovich — Alexander the Conqueror; Pechorin — from Pechora, a river in Northern Russia. It's this latter reference that indicates Pechorin's distance from humanity. He has seen enough of humanity and is sick of it ("As our ancestors rushed from illusion to illusion, we drift indifferently from doubt to doubt") — all that remains for him is travel.

So Pechorin travels. He moves through humanity lucidly, but not imperturbably, knowing moments of calm, and indeed illumination, only in certain solitary places: "The air is pure, the sun is bright, the sky blue — what more does one want, what need have we here of passions, desires, regrets?" He follows his road, without hopes, without aims, that "road of stone" Lermontov evokes in a poem.

It's that stone-road, with its erratic landscapes and eremitic meditation places, I see in Schulz-Dornburg's images taken along the Georgian-Azerbaijan border, on the edge of the Kachetien desert.

3. An Art of Space

Arrived at this point, it would be quite possible to keep to the geographical line, following the course of the Euphrates, that has its source in the Caucasus, down into Mesopotamia (following also, in human terms, Armenian colonists in the Euphrates country, on the Mesopotamian frontier of the Byzantine Empire); or leaving the Caucasus, land of exile, for another land of exile, Siberia, and from there moving out to some Arctic research-stations. It would be a way of revealing the inherent spatial logic of Ursula Schulz-Dornburg's images. But I think by this time we have gathered together sufficient elements. What I want to do now is try to look at things from higher up, describe the space that has opened up during our peregrinations in more abstract terms.

Here and there (notably in an "introduction to geopoetics", Le Plateau de l'Albatros, Paris 1994), I've talked of what I call "the Motorway of the West". This is no place to go back in detail, or even summarily, to an analysis of the whole Motorway. I'll simply stop here a while at the last stage — ours.

For Hegel who, like Thomas Aquinas, had the ambition to make an enormous synthesis of world-culture, a kind of Summa Cosmohistorica, by tracking across the centuries and the continents the "world spirit" (Weltgeist), the prevailing Idea, paramount Reason, was no longer situated in the pure sky of Platonic idealism, it was in movement through time. Progress, with a capital P, was born.

All of the nineteenth century, and a great part of the twentieth, lived according to this conception of things. It's only very recently that belief in it has become totally defunct.

Hence, in the absence of any other great conception, in the absence of any consistent project, a state of things full of blind violence, abysmal punkdom, all kinds of more or less futile games, a cultural context founded on little more than accumulation, and an art based on conceptules.

But there are always, here and there, usually loners and wanderers, individuals with more foresight than others and a larger grasp of things. By the end of the nineteenth century, some minds saw the abovementioned situation coming. They took up a distant stance, and, leaving the Motorway, set out on other tracks, looking for new space.

The one who takes up a distant stance is the Hyperborean. The one who moves away is the Intellectual Nomad. The one who opens up, or at least tries to open up, a new space is the Geopoetician.

Following on from what I said above about the "hero of our time", Pechorin, I'd like to bring forward here two examples, in order to illustrate my proposition: Rimbaud and Nietzsche.

Both try to get out of what Nietzsche calls "the disease of history". Both, to quote Rimbaud, "go on strike". Both are hypercritical of most of what is called "art", with Rimbaud declaring that he prefers "earth and stones". Both move out on difficult paths across the world. Both arrive at a space that is almost anonymous, certainly only with difficulty nameable in common terms. For Nietzsche, it's the Engadine plateau in the Alps, where he enjoys "silence and light". For Rimbaud, it was first the crossing of the Alps, "with only whiteness to think about", then the burning desert of Abyssinia, glaringly empty, ferociously luminous.

The trajectories of both these individuals (who are in fact more than individuals) are exemplary, but curtailed. There's a degree of aberration in their errancy. And it was only at moments that they found the language ("a hermit's language", says Nietzsche) of the space their roads, tracks and paths had lead them into.

As I've indicated, the new space is difficult to define, and it is no easy matter to attain to the geopoetic dimension..

In his book of travels, Bourlinguer, Blaise Cendrars writes about one of the ports (transition places) he passed through: "We were tied up at the back end of the harbour [ ... ] between the Conlundulum, a cargo boat from Panama [ ... ] and the Pathless out of Londonderry [ ... ] at the end of a quay that was in the process of being built or being demolished."

Construction or demolition: there are two possible actions at least going on. What is sure is that nomado-geopoetic space is a lot more complex than the laboratory of "deconstruction" that was one of the marks of the end of modernity, and which only exchanged an orthodoxy for a sinistrodoxy.

With nomado-geopoetic art, there is negativity in the air, but it's a "supernihilistic" negative, which is to say it's a negativity beyond nihilism. As to the "outside" this negativity moves towards, it's much more than the "open air", it's open world. This is the space where the mind is rid of conventional mythical or religious imagery, metaphysical corridors and psychological blockages.

There may remain some slight traces of symbolism (in the Cendrars text, Conlundulum and Pathless may well have been real ships' names, but their symbolical significance is evident enough). Elsewhere, one will perceive, like a watermark on paper, the memory of ancient ways. But for the Intellectual Nomad, there is no turning back, nor is there pile-up of ethnographical, mythohistorical studies, but the way forward, outwards can be charged with memory, and the mind going forward will have worked its way through history out of history. In his Aesthetics, Hegel said that, in the Modern Age, the poetic mind would have trouble making its way across the opaque or trivial mass of social prose. The nomad-geopoetician opens up a way across the territories, moving through areas of transition, renewing ancient paths — on the search for World.

That's how I read Schulz-Dornburg's images.

When the word "art" is associated with the word "nomad", one thinks, in the first instance, of the objects that make up the furnishings of the dwellings in the desert: notably carpets (little cosmogonies) — and the dwelling itself, tent or hut (a concentration of the universe).

Once again, it's essential to comprehend and to see all this outside the frameworks of ethnology or art history.

The thing is to actualize the fundamental.

The most interesting museographic art today is no longer content to simply accumulate objects, it tries to open up space. What I see in this initiative of the IVAM of Valencia is that: the will to reveal the "new space", via a new nomad art, an art in movement, that follows the lines of the world, from stone to star.

Kenneth White

Published in A través los Territorios / Across the territories / Fotografias / Photographs 1980-2002

Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno / Valencia

Heroic Memories

Peter Kammerer, 2002

"The constant reduction in art",¹ working on the line of the horizon, border crossings where water and sky become one and the islands in the river territory of the Tigris and the Euphrates begin to float. Neither sea nor land, forbidden territory, Verschwundene Landschaft (Vanished Landscape), 1980. The stem of the house of Adam, the resistant reed that outlasts skyscrapers. Yet satellite pictures now show how far the work of drainage has advanced: the rage for unambiguousness against the vexation of the marshes. Firm ground for the deluge. Erinnerungslandschaften (Memoryscapes), 2000-01. Men flying in a dirigible over the North Pole: "30 hours non-stop battling against strong winds, through fog, without a single glimpse of sun or sky".² Unable to see, but over the Pole according to the instruments, "we threw out the Pope's cross that we had brought with us and the national flag of Italy, while Trojani uncorked a bottle of advocaat. The gramophone played the Fascist anthem".³ A plunge, searching for land below. Bivouacking on a huge, drifting ice floe. A rescue plane was dashed to pieces. Waiting. "Every bit of wood in the aircraft had already been fed to the fire, and nothing remained of what had been Lundborg's plane but a sad, mangled frame."⁴ A path was forced through the ice by the Soviet icebreaker Krasin, Gramsci's hope in prison in Turi (Apulia).⁵ Childhood memories of flags hung out for rescue: the red cross in the snow, 1945. A weather station with sledges. Transport machines and crews beneath the red banner, rammed into the drift ice. The realm of socialism: "the undreaming coldness of the ice".⁶ The horizon secured in a showcase in the museum of the exploration of the north.

Back into the catacombs. The construction of a darkness that opens slightly to make light visible.

Sonnenstand (Solar Position), 1991-92, a work based on our position in the cosmos. The grammar of a jagged opening, the deciphering of the resurrection. The Camino de Santiago, the scar shared by dervishes and seekers of the Holy Grail. Or the Near East of the earliest Christians, far from Rome, caves of Syrian monks, 15 kilometres along the border between Georgia and Azerbaijan. Grenzlandschaften (Borderscapes), 1998-2000, until 1995 an area for manoeuvres, with grenades and earthquakes as midwives, mountain faces ripped open and light pouring through, the scrawls of Russian soldiers, a land where myths are born. Descent into the underworld, escalators in St Petersburg, Ewiger Weizen (Wheat) in bank vaults. The bareness of the Transitorte (Transitsites), 1997-2001, on the road to Iran, 40 kilometres beyond Yerevan, in April. First in the stranglehold of the Turks, then Stalin, the agony of superfluous races. People standing and waiting. The bus stops made of iron and concrete are Brezhnev's promise. The women groom themselves. Eurydice says: "If you want to photograph me I'll put on better shoes." Living in a container on the Earth's wafer-thin crust. Here and there a vine. A piece of luck. And in all the photographs the invisible legend: "How long will the Earth endure us, and what shall we call freedom?"⁷ The more we ask, the more enigmatic the pictures become.

Peter Kammerer

1. Jean-Marie Straub on Cézanne, interview dated 27.11.89.

2. Samoilowitsch, Rudolf: "S-O-S in der Arktis. Die Rettungsexpedition des Krasin", Berlin n.d., p. 232.

3. Ibid., p. 231.

4. lbid.

5. Letter from Togliatti to Bukharin dated 13.7.1928, and letter from Tania Schucht to Gramsci dated 25.7.1928.

6. Müller, Heiner: "Aiax zum Beispiel".

7. Braun, Volker: "Nach dem Massaker der Illusionen".

Published in A través los Territorios / Across the territories / Fotografias / Photographs 1980-2002

Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno / Valencia

Encounters, Annotations

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, 2002