VANISHED LANDSCAPES

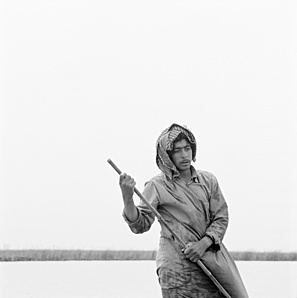

Shatt al-Gharraf, Marsh Arabs

Iraq, 1980

Julian Heynen: Life as it once was in these marshlands — the people and their reed homes — no longer exists. In the history of photography there are numerous examples of things being ‘discovered’ and documented just before they disappear forever. You could call it grief work, be it conscious or subconscious.

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg: I was aware that the life of the Marsh Arabs was disappearing because of the political situation. That was one of the main reasons for going there with my camera.

JH: In this group of works, besides photographs of the traditional marsh culture of this region, there are also images of clay buildings.

USD: I was particularly concerned about the route traced in this sequence of images: from the clay buildings along the Shatt al-Gharraf to the reed structures in the wetlands further south.

JH: These pictures are comparatively narrative and documentary, in the narrow sense of the term. With the exception of the bus stops in Armenia and the metro in St Petersburg, most of your other groups of works are bereft of human beings. But here there are people. How do you see the relationship between humans and the landscape or humans and nature in these images ?

USD: In the sixties and seventies the book Architecture Without Architects (1964) by Bernard Rudofsky (1905–1988) was a kind of Bible for me. In Iraq I was fascinated by the fact that these reed structures went back thousands of years. They embodied an ancient understanding of functions and materials and forms, which evolved to suit the special situation of living by and on the water. By contrast, the actual structures are ephemeral — because of their perishable materials and the natural elements in the lands they occupy. But there was also something else that I was very interested in. You can see it in the photograph of a small, fenced-in patch of field (fig. p. 95). Quite apart from its function or historical significance, I see things like that as works of art.

JH: From solid terrain to fluid terrain — that brings me to the sometimes vast stretches of water that seem to be the real subject of some of your photographs. Is there a connection here with the sandy expanses of the various deserts you have photographed ?

USD: It’s a different situation, but there is a similarity. There’s ‘nothing’ to see, but then you notice, here and there, reeds slowly appearing under the surface of the water. And, like the ziggurats, sometimes you already have a sense of reed structures as you gaze at the horizon. It’s as though there is a suggestion of something — of architecture — in the making.

‘The Verticals of Time’: excerpts from conversations between Ursula Schulz-Dornburg and Julian Heynen in December 2017 and January 2018.