THE LAND IN-BETWEEN

Shoair Mavlian

In April 1980, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg arrived in Baghdad, Iraq, intending to photograph Mesopotamia, the vast expanse of ancient marshland that lay between the converging Euphrates and Tigris rivers. She hired a car, under strict instruction not to travel more than five kilometres outside the city. Needing a solution, and with help from a group of Finnish engineers working in the area, she disconnected the odometer and began a two-week journey south. This simple act of disconnecting the odometer notionally ‘froze time’, disabling and therefore by-passing the restrictions and limits of travel measured in time and space. Without this measurable limitation, Schulz-Dornburg was free to operate outside the imposed restrictions, enabling her to complete her project.[1]

* * *

Time is central to Schulz-Dornburg’s photographic practice, and photography, synonymous with freezing time, is commonly celebrated for its ability to create an indexical imprint of the world.[2] However, time is present in photography in many forms and a photograph could be interpreted as what Daido Moriyama describes as ‘fossils of light’,[3] an object made up of many layers which occurred both before and after a frozen moment. If we take the analogy of a fossil, with each layer slowly built up over a long period of time, we begin to understand how photography functions in Schulz-Dornburg’s work, not as a medium to freeze time but rather as a means to expand time. Schulz-Dornburg offers to the viewer an image as a gateway through which to investigate multiple temporalities, including the context in which the image was made, what came before and what may imminently be about to occur. In her work time is neither frozen, nor linear, but cyclical; she is concerned not with the indexical moment or aftermath, but rather with the layers of time between one great historical event and the next. This in-between period, the lull or down time, often consists of long periods of seemingly insignificant expanse, lasting thousands of years, hundreds of years, or decades, highlighting that the cyclical layers between major events form an important part of the narrative, and are perhaps equally as important as the flashes of activity.

In order to trace these cycles of time, Schulz-Dornburg looks to parts of the world in which time itself seems to have been forgotten. The work explored in this essay is drawn from her projects made in a relatively confined geographic location, notionally following the line demarcated by the 45th meridian east, an area encompassing ancient civilisations bordering positions of modern strategic importance, almost all of which have long been left to decay. Historically referred to as both a gateway and a crossroads, or the ‘lands in-between’, this area was often defined not by its content but by what lies on either side, between Europe and Asia, east and west, ancient and modern, and more recently democracy and dictatorship.[4] Over a thirty-year period, from 1980 to 2011, Schulz-Dornburg travelled to this region, visiting modern-day Armenia, Georgia, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria and Yemen. She documented the ruins of the now abandoned Ottoman railway project in Saudi Arabia, decaying Soviet-era bus stops in Armenia, marsh dwellings in Mesopotamia and, most recently, the remains of the Roman Empire in Syria. As an accumulation of images from a concentrated area of the world, Schulz-Dornburg’s work can be used as a vehicle through which to investigate two connected ideas: time in relation to the context in which they were made, and space, exploring the specific geographical landscape.

The fluid yet measured approach to time and space inherent in Schulz-Dornburg’s practice is connected to the minimal and conceptual thinking that emerged in the United States in the 1960s and grew to prominence throughout the 1970s. In 1967 she lived in New York and was influenced by the art she encountered at private galleries such as Pace and Castelli. She also visited exhibitions of Walker Evans and Robert Frank, which informed her interest in social documentary practice. Later, on her return to Europe, Schulz-Dornburg became familiar with the work of Walter De Maria, Per Kirkeby, Ed Ruscha and Lawrence Weiner. Documentation of two relevant artworks hangs on the wall of Schulz-Dornburg’s Dusseldorf studio. The first is an image of Walter De Maria’s Calendar (1961–1975), an interactive minimalist sculpture consisting of one stationary and one moving stick and a cord containing 365 knots, one for each day of the year. The work, Schulz-Dornburg explains, ‘moves as the year progresses and is a brilliantly simple representation of the ever-changing relationship between time and space.’[5] The second is a photograph of a work by Lawrence Weiner, the opening line of which reads: ‘Having bridged a (the) gap’, alluding to the emblematic gap or the ‘space in-between’. These examples represent two major conceptual threads that appear throughout Schulz-Dornburg’s practice. First, her abstract understanding of movement in relation to time and space, enabling movement and time to be conveyed in still images; and second, the importance of absence and how absence or gaps can be used to ask questions or open up possibilities for investigation.

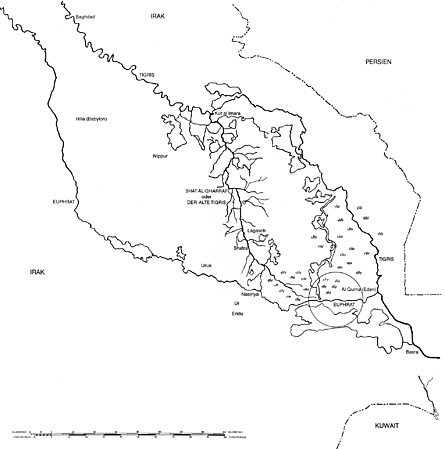

Fig. 3 Mesopotamien, the land between Euphrates and Tigris, (illustration from: Ursula Schulz-Dornburg und F. Rudolf Knubel – Der Tigris des alten Mesopotamien, Irak 1980, exh. cat. Kestner Gesellschaft Hannover)

Fig. 3 Mesopotamien, the land between Euphrates and Tigris, (illustration from: Ursula Schulz-Dornburg und F. Rudolf Knubel – Der Tigris des alten Mesopotamien, Irak 1980, exh. cat. Kestner Gesellschaft Hannover)Copyright: © Ursula Schulz-Dornburg und F. Rudolf Knubel – Der Tigris des alten Mesopotamien, Irak 1980, exh. cat. Kestner Gesellschaft Hannover, ed. Carl Haenlein, Hannover 1981, n. p. p. 145

Schulz-Dornburg exaggerates these metaphorical gaps by emphasising absence through the use of white space when sequencing and planning installations of her work. This sequencing or layout is used as a way to connect images that are conceptually linked but are taken across an expanse of time and space. ‘I have always worked in sequences, as I had particular ideas in my head that I wanted to relate. And I have always worked with a broad time span. The experience of time became a thematic element.’[6] White space or gaps interrupt the sequence, signalling perhaps a break in her journey, a shift in the linear trajectory, or simply as a way to slow the pace of looking. Schulz-Dornburg also explores time in relation to distance, introducing the proximity of these often-abstract locations to the viewer through the use of an accompanying map. (fig. 3) Although the map offers a geographical context, we encounter Schulz-Dornburg’s fluid approach to time as images which are placed side by side in sequence depict locations hundreds of kilometres away from each other. Presented as a journey, each image is a contraction and expansion of time and space that simultaneously reveals and conceals a complicated landscape, with the space or gap between each image left open for the viewer to interpret. Although documentary in form, much of Schulz-Dornburg’s work is a result of her being in and experiencing space. Her images do not depict a journey but her journey through the landscape, her specific route. When discussing this, Schulz-Dornburg describes how ‘through the physical experience of distance, space and representation as conveyed to me by the work of Richard Long I received powerful confirmation of the meaning of travel. Travel is important for me: the further one goes, the clearer positions become.’[7] In that way her work can also be seen in relation to land art and the body’s exploration and experience of the landscape. With this in mind it is important to highlight Schulz-Dornburg’s experience as an outsider to these environments, a position that perhaps allows her to offer a new or different perspective. The importance of this combined experience — first, being physically present in the landscape, and second, experiencing the landscape with fresh eyes — is aptly described by Per Kirkeby: ‘When I move, I break away from all sorts of local provincialisms. What is international or non-provincial is to be found in the air between particular places.’[8]

Iraq

In April 1980, having secured a means of transport, Schulz-Dornburg travelled south down the banks of the Tigris, documenting the journey from Baghdad into the internal marshlands. Inhabited for five millennia, most recently by the Marsh Arabs, the continuous civilisation is referred to throughout ancient and modern history, a subject that first captured Schulz-Dornburg’s attention through Wilfred Thesiger’s book The Marsh Arabs, published in 1964.[9]

The landscape as depicted by Schulz-Dornburg is minimal, characterised only by water, reeds and sky. The images are full of detail, however, as Schulz-Dornburg captures the ripples on the water, reflections of the imposing reeds and solitary figures barely visible in the distance. In this vast landscape, distance and scale are hard to determine, and in many of the images it is hard to make out if the camera is on land or water, moving or still. Despite this complicated and unconventional shooting environment, Schulz-Dornburg is looking for order in the everyday, a characteristic shared with artists associated with the New Topographics.[10] The somewhat organic forms of the floating reed houses are framed and photographed straight on, giving many of the images a uniform frontal perspective; and the sky, perhaps coincidentally, is cloudless, providing throughout the series a consistency similar to that favoured by her contemporaries Bernd and Hilla Becher.[11] In Vanished Landscapes, Iraq, Marsh Arabs (1980), a series of 45 works, we see Schulz-Dornburg refining her photographic language towards a tight topographic framework, only occasionally reverting to a more traditional documentary approach when she turns the camera on her Marsh Arab hosts as they go about their daily lives. (p. 99) This vast project will become her first major body of work, and one feature stands out: the consistent framing of an expansive horizon reaching beyond the edges of the frame. Appearing in her work for the first time here, this use of a flat horizon will become a prominent motif throughout her œuvre. Schulz-Dornburg explains that, ‘For me, the horizon is the zero line of humanity’.[12] This division separating the earth from the sky is used to suggest an illusion of continual movement through time and space, emphasising the importance of each image as part of a wider series, one connected to the next.

Vanished Landscapes, Iraq, Marsh Arabs captures both a terrain and a way of life on the verge of disappearance, and is the result of what Schulz-Dornburg describes as an instinctive desire to record what she believed was under threat. Here it becomes apparent that time in connection with Schulz-Dornburg’s work appears in relation not only to temporality but also to the chronology of history. Her sense of time, her ability to foresee change on the horizon, is extremely important to the ongoing context of her work. Made in the five months before the outbreak of the Iran–Iraq War and during Saddam Hussein’s rise and consolidation of power, the images capture a landscape immediately prior to the changes caused first by the outbreak of war and then later by the draining of the marshland.[13] Although the imminent conflict was not something Schulz-Dornburg could have predicted, she describes how there was a sense of tension and urgency while making the project:

I knew I only had three weeks in the country and I knew I would not be able to return. There was a limited amount of time to take images but also an overarching awareness that major change was about to occur and a real possibility that this landscape, environment and ancient way of life was on the verge of extinction.[14]

On returning to Germany the project was exhibited, and accompanied by a small publication which attempted to draw attention to the unfolding political, humanitarian and environmental situation. However, any effort to gain support for the preservation of the vast wetlands was in the end futile.

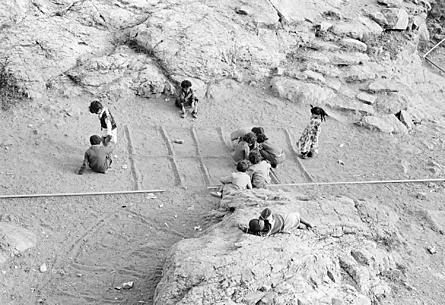

Beyond the marshes, Schulz-Dornburg continued her journey through Iraq and produced another body of work, Vanished Landscapes, Iraq, Mesopotamia (1980), a series chronicling her journey through the vast plains of Mesopotamia and the remains of its cities dating back to 4500 bc, an area often referred to as the cradle of civilisation.[15] Interspersed between images of the sparse, lunar-like landscape emerge the monumental structures of Uruk and Ur, appearing first faintly on the horizon, then coming into clear view as Schulz-Dornburg travels closer towards them. Among the sequence of images appears an unrecognisable structure, ziggurat-like in form. The object in question is a mud brick factory, a comparatively modern structure. The inclusion of the brick factory alongside the ancient temples reminds the viewer how Schulz-Dornburg is not only concerned with history but is equally interested in function, shape and form. When viewing the images, each structure eroded by time and in various stages of decay, the viewer shifts temporally between ancient temples long abandoned and traditional places of work which still fulfil a function today, highlighting the ongoing survival of communities, as ancient and modern worlds exist side by side. Schulz-Dornburg manages to capture in one sequence the cyclical nature of power and the fall of civilisations. Little visual evidence remains of the great cities of Mesopotamia. Once a powerful region of the ancient world the cities are now largely abandoned and relatively unimportant; yet the images remind of a powerful past.

Yemen

In 1986 Schulz-Dornburg travelled to Marib, Yemen, intending to photograph the ruins of Bar’an Temple, colloquially referred to as Arsh Bilqis or the Temple of the Moon God. However, on this occasion timing was not in her favour, because the temple’s proximity to newly constructed gas and oil fields hindered access to the site and limited her ability to work. She captured a small number of images of the temple and surrounding ruins, but the majority of her work from Yemen focuses on elements of architecture and daily life. Schulz-Dornburg’s interest in the built environment was in part shaped by Bernard Rudofsky’s book Architecture Without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-pedigreed Architecture (1964). The book accompanied an exhibition of the same name at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1964 and looks at vernacular or traditional non-Western architecture from around the globe with an emphasis on functionality.

In and around Marib, Schulz-Dornburg photographed domestic dwellings, children playing, and a cemetery where graves are marked simply by placing a piece of rock upright. (fig. 4 and 5) These images of the everyday focus on how landscape and local material inform architecture and design, the approach of which brings to mind Carl Andre’s book Quincey (1973). In Quincey, a small-scale photobook, Andre depicts his hometown on the industrial fringes of Boston, Massachusetts. Andre commissioned a photographer to document the town, historically known for its granite quarries, highlighting the raw materials and natural environment. Made to accompany an exhibition of his sculptures, the book’s front cover image of a granite gravestone raises a clever comparison to Andre’s own minimal sculptures. He emphasises how everyday raw, industrial materials can be transformed through their context, blurring the lines between art and life, function and form. The photographic equivalent to Andre at the time was Lewis Baltz, who exhibited alongside Andre at the Castelli Gallery in New York and whose practice was grounded in finding form in the urban environment.[16] Schulz-Dornburg remembers having come across Andre’s Quincey and was intrigued by its simple yet transformative approach to the everyday.[17] Although something of an anomaly in Schulz-Dornburg’s œuvre, her images from Yemen offer a wider insight into the way she seeks order, structure and form in the everyday environment.

Armenia

In 1996 Schulz-Dornburg arrived in Erevan, the capital of the newly independent Republic of Armenia, with the intention to photograph the ancient churches and places of worship scattered across the country. This idea was linked to one of her earlier projects, Sonnenstand (1991/92), her largest and perhaps most arduous body of work; over a two-year period she travelled across Spain photographing small buildings along the pilgrim trail to Santiago de Compostela, structures dating from the tenth century and representing the combination of Christian, Islamic and Jewish architectures known as Mozarabic.[18] Schulz-Dornburg’s interest in the crossover between different religious cultures and how this is inscribed in architecture coincided with the socio-political movement in the early 1990s which saw the accentuation of differences between Arab — predominantly Muslim — cultures and Western Christianity normalised in mainstream media.[19] Perhaps coincidently, Schulz-Dornburg’s interest in the traces of shared Islamic and Christian histories at the time took her to the Middle East, or the land in-between, the centre of these religious and cultural crossroads.

In Armenia, a country colloquially known as the land of churches, accompanied by a local artist and friend, Schulz-Dornburg set out in a Soviet-built Volga to photograph its ancient monasteries. While driving across the small landlocked country, however, her attention quickly shifted towards what she describes as ‘peculiar and fascinating architectural structures distributed along the roadside’, architectural structures in the form of bus stops.[20] With an almost non-existent railway infrastructure, travel by bus is the main form of inter-city transport in Armenia, where an intricate network of buses or ‘marshrutkas’ connects cities, towns and villages. Isolated on the side of the road and seemingly in the middle of nowhere, the bus stops are very much in use and play a vital role in the daily lives of the country’s inhabitants. Schulz-Dornburg photographed the bus stops as she found them, some of the time with people present, highlighting the ongoing relationship between architecture, function and the local community. As well as documenting everyday life, the series Transit Sites, Armenia (1997–2011) is an observational survey of architectural function and form. Much of Schulz-Dornburg’s work looks at architecture as shelter and humanity’s ability to adapt and protect itself by forging shelter even in the harshest environments. Schulz-Dornburg points out how, in a region noted for its dramatic contrast between snow filled winters and hot summers, the architecture of these structures gives the suggestion of protection while at the same time leaving the users very much exposed. This gentle irony also draws attention to the gap between ideological vision and functional form.

Built in the 1970s and 1980s, these bus stops form part of the country’s Soviet past. Constructed under the leadership of Leonid Brezhnev, they represented the golden age of socialist building. Individual architects were commissioned to design the bus stops either as unique objects or as replicable designs that could be modified to suit the exact location. Architects often used the commissions as an opportunity to experiment and test new ideas that would perhaps not be tolerated in larger-scale commissions.[21] Due either to poor building materials and construction methods, or a lack of ongoing maintenance, these structures, once a symbol of ideology, creativity and spectacle, are now a decaying remnant of a political past whose lasting impact is in contrast to their own physical state. Time exists here in two layers, through the noticeable ageing and decay present on each of the structures, and the theoretical passing of time in relation to the historic moment of a country shifting away from the old, failed regime towards a new independent future. Limbo is something that comes to mind when viewing the images. Some were made just five years after the fall of the Soviet Union and yet the series suggest a country still in shock, having experienced the total breakdown and complete restructuring of life as they knew it.

This experience occurred simultaneously throughout the former Soviet Republics and had a resounding effect on their populations. Having lived through the fall of a modern superpower, Ukrainian artists Sergiy Lebedynskyy and Vladyslav Krasnoshchok describe their experience:

We were taught in school that we were born in the best country, superior to other countries, and that we were sure to secure victory over everybody else. Not long after, the country ceased to exist.[22]

This experience of drastic change seemed to many people as if it occurred overnight; it suggests a complete break in chronology, a total upheaval, in which our understanding of linear, chronological time is ruptured completely, where before and after are in stark contrast to one another.

As well as highlighting this rupture and the subsequent state of limbo, Schulz-Dornburg’s work, made over a ten-year period, also highlights transition. As the historian Serhii Plokhy suggests: ‘The collapse of the Soviet Union, like the disintegration of past empires, is a process rather than an event. And the collapse of the last empire [the Soviet Union] is still unfolding today.’[23] Schulz-Dornburg’s extended period of documentation in Armenia, capturing glimpses of transformation over time, highlights how in the long cycles of time transitional moments can extend for years or even decades.

The desire by the newly independent nations to erase many of the traces of their Soviet past highlights how the built environment often outlives the ideological concept of its creators. It is also important to note that total erasure of a past ideology, be it religious or political, is hard to achieve. For example, the Church and religious iconography were largely discouraged during the Soviet era, yet on closer investigation it is relatively easy to discover references to the traditional architectures of the Christian Church hidden in plain sight. The umbrella structure, a relatively common and very durable bus stop design, derives its angular conical shape from the circular roofs of traditional Armenian churches.[24] (fig. 7) This transposition of religious symbolism into functional everyday form was produced en masse and highlights how difficult it is to achieve erasure of the past.[25]

Transit Sites, Armenia was different to much of Schulz-Dornburg’s work, where she only visited the country for a short amount of time in order to make a specific project. She returned to Armenia several times between 1996 and 2006 and made in excess of fifty works. Schulz-Dornburg presents the series in uneven grid-like installations reminiscent of constructivist design. In this way the installation emphasises both the concrete, brutalist architecture of the bus stops, and the overarching aesthetics inherent in Soviet ideology.

Georgia and Azerbaijan

In 1998, following one of her trips to Armenia, Schulz-Dornburg travelled to neighbouring Georgia and from there to the eastern region of Kakheti, where she made the series 15 kilometers along the Georgian-Azerbaijanian Border (1998/ 99). As the title suggests, she travelled along the Georgian side of the border of these two newly independent nations to photograph the cave dwellings which fall between or on the borders of both countries, and which since independence had become a minor issue of contention.[26]

Scattered across a low-level mountain range, the isolated network of cave dwellings is said to have been founded in the sixth century by St David Gareja, sometimes referred to as Davit-Gareja, one of thirteen Assyrian monastic missionaries who arrived from Mesopotamia to spread Christianity. The missionaries sought shelter and protection in the caves, formed from a series of naturally occurring sandstone caves. The area was a working monastery until the end of the nineteenth century, falling out of use in the twentieth century due to the de-emphasis of religion during Soviet rule. More recently, in the latter half of the twentieth century, the area had been used by the Soviet Army as an artillery training range, apparently due to its similarity to terrain in Afghanistan.[27] Following the breakup of the Soviet Union and the resulting redrawing of borders, the ancient monastery found itself at the meeting point of two opposing national frontiers.

Shelter, and the way in which humans seek out, craft and create shelter, is central to Schulz-Dornburg’s practice. From the beginning, whether in relation to permanent architecture or temporary refuge, Schulz-Dornburg has been interested in how humans adapt even the most inhospitable surroundings. The caves in 15 kilometers along the Georgian-Azerbaijanian Border perhaps have an even more direct resonance for the artist. Born in Berlin in 1938, Schulz-Dornburg experienced the Second World War as a child. When recalling her memories of the final years of the war she describes her time spent in the very south of Germany, on the border with France, essentially ‘on the frontline’[28] of fighting. With her town destroyed by Allied bombing, Schulz-Dornburg and her family hid in underground shelters. ‘Caves were always shelter for me, they were something that I lived with, we used to hide in them when we were children because we lived so close to the border.’[29] Humanity’s universal need for shelter is at the centre of Schulz-Dornburg’s thinking, and her work acknowledges the long history of architecture’s essential role in human existence, highlighting the role of these spaces beyond the basic needs of shelter, and investigating how different architectural structures can take on multiple purposes, as places of worship and solitary spaces, but also as transient, shared spaces.

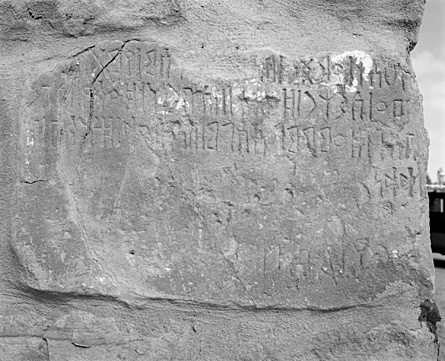

Like in Sonnenstand (1991/92), light and the position of the sun are crucial to this work, illuminating the otherwise dark, unreadable spaces, some with room for only one single inhabitant. Time has taken its toll on these places of solitude, and graffiti, both ancient and modern, lines the walls: in some instances well preserved frescos with text dating back to the birth of the Georgian alphabet, in other locations more recent Cyrillic text, presumably inscribed by military conscripts. (fig. 8) Here we interpret multiple histories simultaneously as the palimpsest of text and image co-exists, highlighting both the passing of time and the change of use and function.

In the series, the internal views of the caves are interspersed with spectacular landscape images, of views looking out over a lunar landscape, across the border into Azerbaijan. (fig. 9) Although not explicitly outlined by Schulz-Dornburg, the vantage points from which these landscapes are taken emphasise the height and isolation of the caves, and in turn draw attention to how difficult it is to reach the forbidden land over the border. In fact, several of the caves do cross the border into Azerbaijan, causing difficulty for visitors to the area. With these subtle hints, 15 kilometers along the Georgian-Azerbaijanian Border raises questions around the arbitrary nature of borders in a region that has long been marred by external cartographic power. Stalin notoriously redrew borders and reallocated land as part of a much larger power game between Soviet states and ethnic minorities.[30] Perhaps more infamous is the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which was drafted in secret during the First World War and signed by Sir Mark Sykes and Francois Georges-Picot on 8 May 1916. The accord laid out a plan to divide parts of the Arab world into British and French spheres of influence in preparation for an Allied victory. Although the agreement never materialised it did form the basis for colonial powers to carve up and divide parts of the Ottoman Empire, Syria and Persia, what is present-day Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey. Seen as abstract ‘lines drawn on a map’ by colonial powers with no real cultural understanding or geographical surveying of the land, the borders eventuated from the Sykes-Picot Agreement are considered by some academics to be a contributing factor to ongoing conflict in the area to this day.[31]

Saudi Arabia

In January 2003 Schulz-Dornburg travelled to Saudi Arabia to retrace the Ottoman Railway which once linked Damascus to Medina. The result was her series From Medina to Jordan Border (2002/03, pp. 59–74). Begun in 1900, the railway reached Medina in 1908, and was one of the great engineering projects of the Ottoman Empire. However, its construction, destruction and eventual abandonment reveal a complicated and layered history of past alliances, fallen empires and colonial interventions, all of which are present in Schulz-Dornburg’s images.

Built under the direction of German engineer Heinrich Meissner, the railway was designed to connect Damascus to Mecca, linking Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, to the Holy City. It was intended to serve pilgrims while at the same time strengthening the empire’s administrative and military hold over the Arab region. By the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the Hejaz Railway Station was opened in central Damascus and the 820-mile stretch to Medina was complete, at its height carrying 300,000 people each year.[32] However, apparently encouraged by British colonel T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), the line was routinely attacked by local Bedouins, both as an act of destruction and to utilise the raw materials. Following the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire the railway was largely abandoned. Left in a state of disrepair, and due to the harsh environment, it quickly fell into decay.

When, 85 years later, Schulz-Dornburg retraced the route of the Hejaz Railway, she discovered that although much of the track had deteriorated, had been removed or swallowed up by the desert, the station buildings remain standing, without purpose in the expansive desert landscape. The stations all follow a standardised design, featuring an ‘L’-shaped structure presumably designed for functionality and durability. The images, shot against the flat horizon of the desert, reveal the vast isolation of the harsh and unforgiving environment, only occasionally sighting a piece of track or a locomotive left to rust. Although the images reveal the harsh realities and the downfall of empire, they also speak of a much longer cycle of time and decay. As living memory of the Ottoman Empire fades, the physical objects which it built still haunt the landscape.

In From Medina to Jordan Border, Schulz-Dornburg reminds the viewer that physical history is hard to erase. Architecture and the built environment that, on the surface, is there to serve the people, also serve a more sinister function. With the benefit of hindsight it has been suggested that infrastructure is often used by imperial powers to cast their web over vast regions in an attempt to widen reach and consolidate power, often in the name of modernisation.[33] Schulz-Dornburg’s project also speaks of failed ambitions, misjudgements and the inability of humans to tame inhospitable landscapes. It reminds us that modernisation is not always greeted with open arms; and what the Ottoman rulers saw as modernisation was interpreted by the locals as a threat to their position as the gatekeepers of centuries-old migratory routes and traditions. Having an interest in anthropology and archaeology, Schulz-Dornburg was drawn to the historical significance of the route. The route itself had been in use for centuries, travelled by foot, camel and caravan, as part of both the economic Silk Road and the pilgrimage to Mecca. Schulz-Dornburg documented the traces of these past journeys, from a time long before the railroad was conceived, capturing markings and graffiti carved into rocks in Arabic, Aramaic and characters from ancient languages no longer legible. (fig. 10) Although not included in her final edit, Schulz-Dornburg’s close-up images of these ancient graffiti found on rocks and informal resting places along the route illustrate how layers of history exist simultaneously in one place, captured in one image, visualising what she refers to as ‘vertical layers of time and history’.[34] Casting her lens over the seemingly barren desert landscape she reveals what is hidden or overlooked, fracturing the linear notion of time to expose multiple histories in one frame. From Medina to Jordan Border simultaneously depicts her journey in 2003, events which occurred in 1917, and the ancient traces which came before, highlighting how, although our means or methods might change, the historic routes of migration and trade largely stay the same. By doing this, Schulz-Dornburg ruptures time, using the image as a gateway to see multiple temporalities and multiple histories, revealing with her camera important traces just below the surface which demand closer investigation.

Like Ed Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1962) and Mark Ruwedel’s Westward the Course of Empire (1996–2006), Schulz-Dornburg’s From Medina to Jordan Border set out to retrace the railway’s exact route through Saudi Arabia from Tabuk in the north to Medina in the south, with the intention to photograph every train station along the route. However, things in the region are often never straightforward. At the end of January 2003, Schulz-Dornburg had permission to photograph and a chaperone to drive her along the route. However, one week into the project, US President George W. Bush announced the imminent invasion of Iraq, prompting the project to be cut short and eventually abandoned. Again, we are reminded of Schulz-Dornburg’s uncanny relationship with time, or, rather, her ability to foresee that instability or change is on the horizon.

Iran

In 2006 Schulz-Dornburg travelled to Iran, compelled by Erich F. Schmidt’s book Flights Over Ancient Cities of Iran (1940), a surprisingly modern book that combines text with 119 mostly aerial photographs, some of which are overlaid with red lines marking out the corresponding flight paths in relation to the images. The formal yet abstract nature of Schmidt’s mapping process appealed to Schulz-Dornburg’s interest in visually mapping the landscape. In Iran she set out to photograph the Tomb of Cyrus in Pasargadae, believed to have been constructed in 530 bc. The tomb is thought to hold the remains of Cyrus II of Persia, the founder of the Persian Empire. However, when she arrived in Pasargadae the famous tomb was undergoing restoration and covered in scaffolding. Instead she continued her journey south to Gur-e Dokhtar, Jareh, south of the Fars province, and photographed an alternative tomb, similar in architectural style but slightly less grand in scale. It is thought this tomb could be a precursor to the famous Tomb of Cyrus, and perhaps belonged to an ancestor of Cyrus the Great, such as Teispes or Cyrus I.[35] Photographed in what has by now become her signature style, front-on and perfectly aligned in the centre of the frame, the two images depicting adjacent sides of the tomb represent symmetry and order. However, as much as Schulz-Dornburg advocates order, disorder holds an equally important role, in this case disrupting the diptych with a third image showing a figure in the background. (fig. 11) Now what seemed like a relatively modest structure is revealed to be monumental in scale, immediately increasing its importance and status. This reflects its historical importance, as it is commonly believed that the Tomb of Cyrus was popularised by Alexander the Great, who sought out the tomb of Cyrus in order to pay respect to the great ruler as he himself conquered Persia more than two centuries later.[36] The tomb’s architecture is believed to include traces of influence from across the region, highlighting instances of cross-cultural fertilisation, an idea which is linked to Schulz-Dornburg’s wider investigation of intertwined histories and the cycles of time and empire throughout history.

In the case of both Yemen and Iran, for reasons beyond her control Schulz-Dornburg made relatively few images, leaving a gap in her œuvre. This void tells an interesting story, itself revealing the complexities of travel, permission and a window of time which either makes her work possible or, in these two rare cases, impossible to complete. Regardless of the fact that Schulz-Dornburg did not achieve her intended project, these images work as a glitch or rupture which adds contrast to the fuller areas of the larger narrative.

Syria

First in 2005, and again in 2010, Schulz-Dornburg travelled to Syria, visiting the ancient city of Palmyra on both occasions. Palmyra, situated on what was once the southern frontier of Roman Mesopotamia, was a far-flung outpost of the Roman Empire and now forms part of modern day Syria. The ruins of Palmyra are a world-renowned archaeological site and have been visually documented by photographers as far back as the first albumen prints of Louis Vignes in 1864.[37] In an area with such a wealth of visual stimuli Schulz-Dornburg, like those before her, photographed the iconic tableaux, the Temple of Bel, and the Valley of Death — one of her few images made in colour. Here her photographs of these landmarks join and add to the wealth of visual documentation of the city which already exists. Rather than focusing only on the iconic structures, Schulz-Dornburg also drew attention to the less elaborate constructions, passing over the famous Tower Tombs built to house the remains of the wealthy and concentrating on the more modest tombs, which, due to their low centre of gravity, remained largely intact. Schulz-Dornburg photographed the tombs from all four sides, her frontal approach again emphasising the symmetrical architecture of the structures. Her interest in the mundane continues when, on what some would consider one of the greatest promenades ever built, Schulz-Dornburg turns her camera towards an unassuming stone wall. The simplicity of this construction is important, symbolising how a solid structure is at the root of architectural form. In these close-up images of the wall we no longer see a city of ruins but a city built on strong foundations, precisely planned and technically advanced. (fig. 12) However, the images also raise the question of authenticity. Within the layering of history, time is difficult to decipher. This is what Schulz-Dornburg describes as ‘vertical history’ or the ‘vertical timeline’, a term used by the artists to describe how history is stacked one layer on top of the previous. Here we begin to question if the wall was part of the original structure or was it built centuries later ? And does it matter ?

* * *

Throughout history, major events occur which change the physical and social landscape beyond recognition. In retrospect, these events are often perceived as ‘points of no return’.[38] In modern times, examples of ‘points of no return’ could be events such as the First and Second World Wars (including the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki), the fall of the Soviet Union, and the terrorist attack of 11 September 2001 on New York’s Twin Towers. In ancient times the fall of the Roman Empire in 410 ad was also one such marker point. In 2010, Schulz-Dornburg travelled to Syria and photographed Palmyra, the iconic outpost of the Roman Empire, one year before the outbreak of the civil war which still grips the country today. In 2015 and 2017, several years after Schulz-Dornburg’s trip, much of the remains of Palmyra were intentionally destroyed while under the occupation of the Islamic State of Syria and the Levant (ISIS), eradicating the relics of the 4000-year-old civilisation. The site’s guardian, Khaled al-Asaad, a renowned archaeologist and retired director of antiquities, was born in Palmyra and lived there until his death in 2015 at the hands of ISIS.[39] This act of iconoclasm means photographic documentation of Palmyra, such as the work by Schulz-Dornburg and others, forms an archive of cultural history parallel to but equally as important as the original photographic projects.

If nothing else, the recent destruction of Palmyra cements Schulz-Dornburg’s theory of time as an ongoing cycle. Despite the passing of decades, centuries or millennia, time is not frozen and nothing is safe, and destruction often comes full circle. This cyclical understanding of time in Schulz-Dornburg’s work also means that the context in which we view her images is fluid and ever-changing. Her work, viewed in 2018 from our current sociocultural and political position, will no doubt take on a different meaning and perspective after the next major point of no return.