Let me preface my thoughts with an autobiographical note to explain the angle I take in viewing Ursula Schulz-Dornburg’s series of photographs. Much of what is found in these pages can be traced back to our conversations, in which we would frequently take journeys of the imagination together, visiting the countries we had both worked in. We explored wildly different times and places in our travels, and if you wish to retrace these traces with me, I invite you now to follow me on such a journey to a rather peculiar place in southern Iraq. For this place and the stories told about it stand for a way of looking at the world that joins us in friendship.

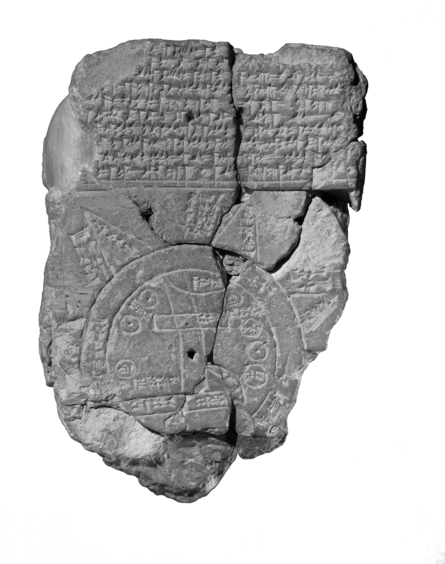

The place in question is a hill ruin on the Euphrates, 200 km north-west of Basra and not far from the small town of Nasiriya. On it lie the remains of the ancient Sumerian city of Eridu, once founded in the sixth millennium BC and considered for many thousands of years to be where all of humankind began. In this city, there existed a temple for the god Enki, the god of wisdom, who had once brought life-giving water to Mesopotamia. The temple contained images of Enki showing him with the two great rivers Tigris and Euphrates pouring from his shoulders. To the Sumerians, Eridu was the birthplace of human history and the wealth of the Fertile Crescent. As Mesopotamian urban culture changed from the fourth millennium BC onwards, the centre of the world slowly migrated northwards until it arrived at Babylon many millennia later. Eridu fell into ruin and only traces of its former grandeur remain visible today. In the eighth century BC, when Eridu was already declining, a map of the world (fig. 1) was created in Babylon. Now on display in the British Museum, it shows a circular world, surrounded by the bitter river (marratu), beyond which islands and regions reach out into mythical space. Within the circle, a central continent shows the Euphrates and various cities, with Babylon being marked out as the centre.

A number of years ago, three strange events played out at Eridu. The little town of Nasiriya not far from the ruined mound suddenly became known to the world at large during the first year of the Second Iraq War. On 23 March 2003 a US-American unit was ambushed and several soldiers killed or wounded. Among the wounded was 19-year old Jessica Lynch. Nine days later, she was liberated from a hospital by Special Forces and celebrated in the US as a national icon of female bravery. A few months later, however, an investigation commission had to admit that the story of the young soldier had transpired somewhat differently. She had not suffered a great ordeal, but had in fact been patched up and saved by Iraqis. During her hearing in Congress in 2007, Jessica Lynch accused the Pentagon of having spread propagandistic lies about her and the Iraqis.

A year after this hearing, in June 2008, an international team of scientists boarded a helicopter on the British air base at Basra and flew out to Eridu to assess the impact the Iraq War had had on the ancient ruins in the region. The team was headed by John Curtis, at the time keeper of the Middle East Department of the British Museum in London. The photographs published on the Museum’s website show a drab settlement mound, pockmarked by erosion and surrounded by little more than desert. Only if we rewind time far back, we can imagine that this was once the site of a city flourishing in a verdant, bountiful landscape. The nearby Lake Hammar and the marshes on the Persian Gulf are considered the ancient model for the descriptions of the Garden of Eden in the Bible. After the First Iraq War, this area saw dramatic changes. When the war began in 1991, the Shiites living in these marshes took the opportunity to rise in revolt against the Sunnite regime of Saddam Hussein. The retaliation was brutal. Besides horrendous massacres of civilians, the marshes were drained by two new canals that collected the river water and channelled it into the Persian Gulf. Faced with the destruction of their natural environment, the local population dwindled due to emigration. When Saddam Hussein fell in 2003, the canals were breached and the marshes flooded once more, but only a fraction of the original population returned and nature was slow to recover. And on 26 November 2014, a sombre headline of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung duly noted that ‘paradise is here no longer’.

* * *

This combination of a story that takes us back millennia with select episodes of contemporary history is an example of a way of accessing spaces that I and the artist have always shared. As our many conversations have revealed over the years, we are both fascinated by the traces humans have left behind in landscape and space, accumulated by the progress of history, and by our interest in drawing close attention to the current situation in these spaces. In my own archaeological work in various parts of Turkey, which involved conducting so-called surveys that document only those remains of the past visible on the surface, I became increasingly intrigued by the layers of history, as well as their organisation and reconstruction. In conducting this research, I was reading the surface of the earth as a palimpsest of human settlement history. At the same time, I was also impressed by the insights this deep-dive of 3,000 years into our past revealed about the contemporary concerns and troubles of the current population. As an expert for the history of Antiquity, my interest is directed also at contemporary events that seem to have no immediate connection to other layers of history, and to the events of Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Saddam Hussein’s terrible revenge, Jessica Lynch’s experiences, and the British Museum expedition cannot be tied to the history of ancient Eridu directly, but they all leave traces in the landscape that add to those left by the city. All these little pieces are part of the long historical trajectories of human spaces that demand our attention. Since their complexity prohibits a grand master narrative, the historian is called to engage with these individual fragments of history. In doing so, our primary concern should not be with their place in the big picture. Even if we cannot place it at all and the fragment seems completely isolated, it should not be discarded as an object of inquiry. Proceeding in this way generates insights, descriptions and of course images that reflect the plurality of meaning inherent in human existence and history. They provide readers and observers with opportunities to create their own connections and take part in weaving the fabric of historical memory.

* * *

Such deeply entangled meshes of memory emerge also when we engage with the works of Ursula Schulz-Dornburg. Spaces and places perceived and photographed across many years are here woven together. Let us consider a few of her series in this light.

When she travelled the alluvial plain of Euphrates and Tigris in April of 1980, shortly before the Iraq-Iran War broke out in September of that year, she first created a series of photographs of ancient settlement mounds. The pictures pay great attention to the traces of history one can encounter all over a landscape that seems drab and parched at first glance — we see roads and paths, remains of buildings and shards of pottery, tombs left by ancient cultures, and many other details. Besides the ancient ruined settlements in the Euphrates valley, her interest was also in the marshlands on the Persian Gulf that were mentioned earlier. Considering the catastrophic transformation of this area after 1991, the title she gave the series in 2002, Vanished Landscapes, Iraq, Marsh Arabs becomes painfully clear. The photographs show the old marshlands intact, overgrown with reeds and endlessly rich in water. Dwellings and silos built from natural, local materials in seemingly archaic forms serve to imbue the landscapes with a timeless quality. The composition of the images, with their central horizon lines and recurring bright skies reflected in bodies of water, helps to create an ethereal, magical atmosphere of endless tranquillity. Buildings, reeds, boats and settlements seem to be entirely still. Even the few people we encounter, either up close or at a distance, seem to exude an aura of grave and concentrated quiet, detaching them from the flow of time. Nevertheless, one instinctively creates a direct link between them and the rush-built houses, their interiors housing unknowable secrets. A number of photographs of these interiors reveal comfortable living spaces, which the light slanting through the windows infuses with an almost sacred atmosphere. Despite the scanty and often remote humans visible in these shots, the combination of horizon lines, reeds, water and architecture exudes a powerful sense of coming close to all things human. The horizon line, the artist wrote in 2002, was to her the zero line of humanity. The disturbing, paradoxical feelings the Verschwundene Landschaften, Iraq, Marsh Arabs series evokes with its near absence of humans are fuelled precisely by this statement made image. One immediately finds oneself challenged to envision the life lived by the people inhabiting this landscape.

The landscape photographs taken on the Euphrates and in Saudi Arabia encourage the viewer to gaze humbly out into the eternity of these places and note the fleeting nature of these delicate traces of history humans have left upon them. The significance of eternity for Ursula Schulz-Dornburg comes more clearly into focus if we turn to the photographs she took of Mt. Ararat in 2006 from Khor Virap in Armenia. The fabled mountain persists as a symbol of eternal endurance, despite its changeable history, which ranges from Noah’s ark, to mentions in ancient oriental epics, the rise of Christianity, and even the tragic Armenian genocide. Its aspect constantly changing in light, clouds and ice, the mountain seems to present itself as an ever-remote monument of nature itself. But Ursula Schulz-Dornburg has unearthed comparable intensity also in the miniscule. Her series Ewiger Weizen (Wheat eternal, fig. 2), the only installation in her portfolio, shows close-up views of grains and ears of wheat, photographed in the seed collection at St Petersburg that documents many thousands of years of human nutrition and agricultural history. The erotic dimension the photographs reveal in the cereal structures, with their shapes reminiscent of the female sex, and the entrancing architecture of the ears echo a lost historical diversity that now exists only in clinically catalogued sorting tins. The series offers a remarkable insight into an archive of the traces humans have left across the world’s fertile landscapes in their struggle to feed themselves.

This exploration of the traces of human history saw an impressive variation in 1991/92, when Ursula Schulz-Dornburg realised a project of an entirely different kind. Titled Sonnenstand . The zero line of the horizon was here replaced with a closed space and the passage of time itself, ephemerality, took centre stage. The timeless landscapes of Mesopotamia made way for glowing spots of light, staged in the small chapels that line the Way of St James as it passes through the Pyrenees. As the light slants through the small windows set high in the wall of the apse and falls into these sacred spaces, its angle of entry signals the time of day. Across a series of images, the entire passage of a day is made visible. The same is true of the change of the seasons, which can be traced by paying close attention to the altitude of the sun’s rays. As a whole, the series is full of dramatic mystery. Like the open landscapes of Mesopotamia, these enclosed spaces make the proximity of humans intensely palpable. It was they who built the architecture, they who learnt to read the passage of time from rays of light. Only humans created these spaces and the conditions necessary to perceive it either in Christian contemplation or through lens and film. Without humans, Sonnenstand is inconceivable. It is par for the course, that Ursula Schulz-Dornburg then proceeded to fathom other dimensions of human constructions of space in her project 15 kilometers along the Georgian–Azerbaijanian border (1998–2000, pp. 161–176). The vaults monks have carved from the rock of the Armenian Caucasus show light bouncing curiously off the lingering traces of chisel strokes, off alcoves cut roughly from the walls and off the porous surfaces of the roughly smoothed rock walls. Unlike in the Christian chapels of Spain, here the viewer’s gaze is drawn less to light and time, and more to the space and the artificial shape imposed upon it by the strenuous efforts of human hands.

The Armenian bus stops Ursula Schulz-Dornburg photographed at around the same time and published in the series Transit Sites, Armenia feel like human signs that are entirely out of place in the often dreary landscape and their immediate environs. These buildings create places that are at first entirely opaque to non-locals. Some of the photographs show people, for whom these architectural markers clearly offer an unchallenged point of orientation that helps them navigate space. Openly facing the photographer and her lens, they emanate self-assurance, security and even elegance that directly contrast with the decaying and even ruinous bus stops. The juxtaposition between the Soviet concrete and steel structures and the self-assurance of the waiting people immediately raises the question of what their day-to-day life beyond the bus stops might look like. The place they are waiting at seems to merit no particular attention, reflecting a posthumously published insight of Robert Musil, written in 1936: that with all humans ‘the set dressing of our consciousness loses the ability to play any part in this consciousness’. Through her photographs, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg gives back to the people waiting at these bus stops a place that they have since long stopped paying attention to, places that have become a naturalised part of their routines. The photos showing people riding escalators in St Petersburg pose a similar challenge to the observer, who learns nothing of their origins and goals. These people also seem to have fallen out of the very passage of time — in some cases one cannot even tell if they are going up or down.

The re-entrance of a place into consciousness can be attained by telling a story or by creating Memoryscapes, St Petersburg, as did the series of the same name, made in 2000–2001. In the Arctic-Antarctic-Museum in St Petersburg, dioramas recall a spectacular emergency rescue mission. Ursula Schulz-Dornburg captured these re-staged scenes with a small amateur camera and then heavily enlarged the photographs. The blurred silhouettes this creates give the viewer the impression that they are looking not upon its re-staging, but upon the actual arctic landscape. The photographer confesses that these scenes brought back memories from her own childhood in the last year of the War in 1944/45: pictures of wounded men and tents weighed down by snow. Added to these were images from films of the 20s and 30s, set in the ice and snow of Mont Blanc or Piz Palü. The fusion of internal and external landscapes of memory allowed these photographs to create novel landscapes on a new level.

* * *

Grains and ears, rocky caves, open landscapes, tiny chapels, Buddha statues (fig. 3), religious buildings in Sulawesi, tombs in Palmyra, bus stops, structures in the nuclear test area at Semipalatinsk, commuters on escalators and innumerable other subjects — the thematic variety of the series shot by Ursula Schulz-Dornburg is immense and impressive. But despite this diversity, one can, as we have seen, find recurring elements and concerns. One of these is travel, constantly being on the road in East and Central Asia, Mesopotamia and Spain. Distance, space and the unknown open the senses to things that would remain unseen in familiar environs. From our plans for a joint journey I know that Ursula Schulz-Dornburg takes her time in exploring new places, circumspectly orients herself in the unknown (literally so), and takes note of the changing light.

All her projects have in common that in the landscapes, architectures and even in the photographs of grain, humans are at the core of her interest. Their spaces and traces are what she seeks out and attempts to frame. Behind all this lies what she once called her ‘parallel universe’. Referring to her engagement with good causes that took her to Amsterdam’s adventure playgrounds in the 70s and 80s and into the day to day life of heroin addicts, and that she continues to actively live to this day. She observes the social cleavages of our times with great acumen and is never shy to voice her indignation about injustice and the grave blunders of humankind in conversation. The ancient, archived ears of grain and the precarious structures that dot nuclear testing grounds (Chagan and Opytnoe Pole, both 2012) may stand as examples of her documenting such blunders: the loss of sanguine diversity and the terrors of militaristic architecture.

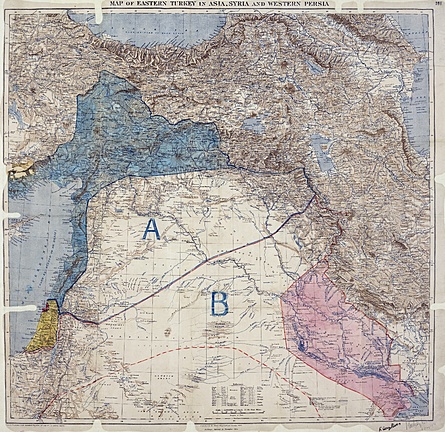

Due to her travels through Mesopotamia and the persistently recurring wars there, she is personally appalled at how the Near East was divided between the British and the French in World War I, after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and at what drastic consequences this continues to have. In 1915 Mark Sykes and François Picot agreed upon a line drawn by Sykes as the border from the Mediterranean to Western Mesopotamia. The area north of this line was to be French, the South British (fig. 4). The borders created in that moment persists until today and have caused incessant conflict. The ancient Babylonian map of the world we saw above has been cut straight through the middle and even the division of Iraq in 2003 after the Iraq War drew upon the same line as its basis. When we were discussing this episode with Mark Sykes, Ursula Schulz-Dornburg reminded me of the famous treaty of Tordesillas made by Portugal and Spain in 1494. The two naval powers drew a line through the Atlantic from the North to the South Pole, dividing the globe into a Spanish and a Portuguese half — another irritating act of human hubris and political arrogance.

It comes as no surprise that her deep interest in politics and society is refracted back at the viewer of her work. The various layers of space, architecture, history, people and the traces they have left all over the place are thus supplemented by an interplay between inside and out — in two ways. On the one hand, the artist herself picks up on things in her surroundings that come from within and grow out of significant memories and her own Erinnerungslandschaften (Memoryscapes). On the other hand, she has always tried to gain insight into the inner workings of events, make them visible, and find an outside perspective.

When engaging with her photographs, one sometimes gets the feeling that a place, a space or a landscape seem uncannily, archetypically familiar. Or one is surprised by their complete unfamiliarity, by one’s complete failure to understand at a glance, which invariably breeds the wish to fit what one sees into one’s own experiences. Doing so requires a deeper, almost archaeological engagement with the photographs, gradually cutting through their layers and unravelling the references buried under the surface. At least part of the artistic merit of Ursula Schulz-Dornburg’s work thus undoubtedly lies in how in touch it is with humanity and how it shows the viewer the complexity of human spaces, teaching us to see these spaces and our own day-to-day life in their full profundity.